Introduction

The plan for premature

retirement of the RAAF's F-111 fleet is the most far reaching force

structure change for the RAAF, and the ADF as a whole, seen for many

decades. As such it will have significant consequences for the RAAF

many

of which are not widely understood, even in RAAF circles.

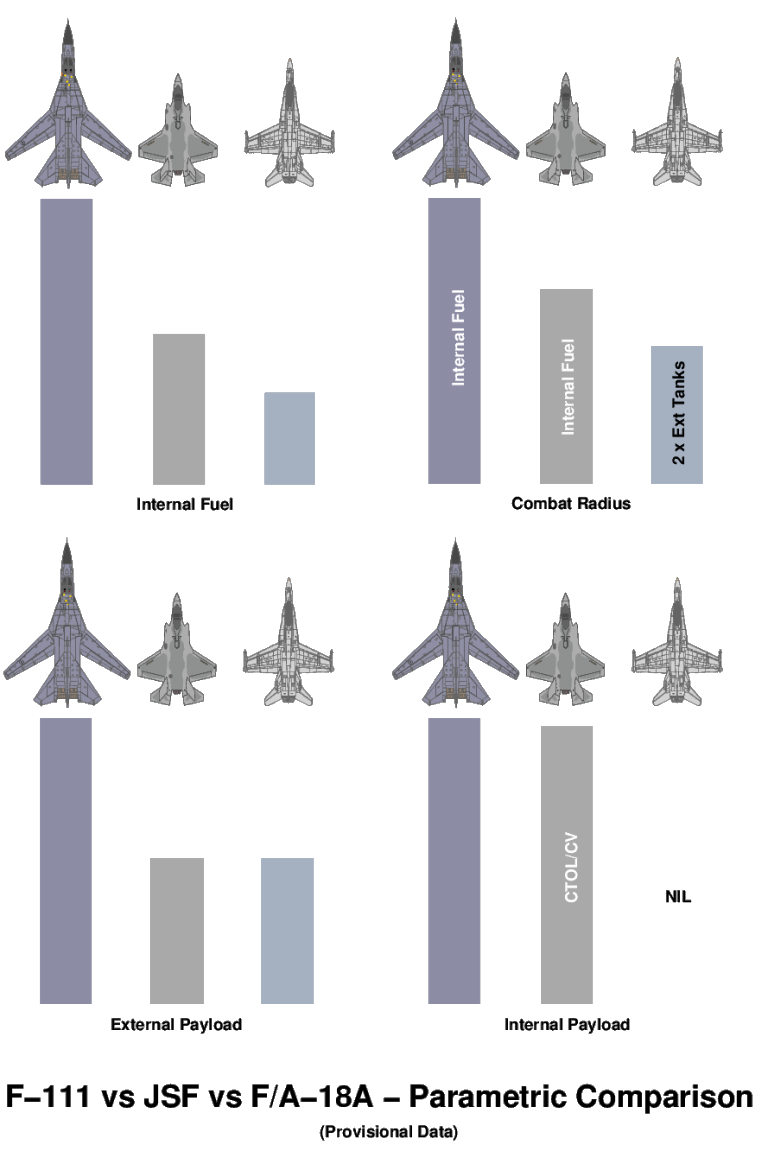

For three decades the F-111 has been the

backbone of the RAAF combat fleet, providing a strike capability with

no

peer in this region. In context, Australia's thirty plus F-111s provide

around 50% of the RAAF's aggregate strike capability, and a long range

and persistent precision guided munitions delivery capability without

aerial refuelling tanker support. In budgetary terms, the F-111

capability is a bargain, costing around 3.5% of the annual Defence

budget to operate. Providing the equivalent capability using smaller

fighters like the F/A-18A or JSF supported by tankers typically costs

around 70% more, per aimpoint hit, than using the F-111. Removal of the

F-111 chops down RAAF strike capability against the White Paper goal of

four years ago by 40% - if we believe Air Force leadership statements –

or closer to 60% if we employ hard quantitative measures.

Much has been said and written about

this issue, in the broadcast media, trade press, daily press and in

parliamentary committee submissions. That the debate has attracted such

interest, and persisted for over a year now without abating, indicates

very clearly that there is little enthusiasm for the early retirement

of

the F-111 outside the corridors of Russell Offices. Indeed, with the

exception of a handful of advocates largely associated with the current

Air Force leadership, there are very few who would support the decision.

What has emerged over 12 months of

public debate on this issue is that the case brought against the F-111

last year was centred entirely in non-sequitur arguments,

mis-interpretations of technological and regional trends, and a good

number of myths accepted as fact within the Defence bureaucracy. That a

decision of such strategic importance to the nation was sold to Cabinet

on the basis of so defective a rationale raises good questions about

the

intellectual rigour underpinning the whole plan for the future of the

RAAF.

The current budgetary allocation for the

replacement of the F-111 and F/A-18A with new combat aircraft now sits

roughly at A$12bn to $15bn, putting it in the category of more than ten

Snowy Mountain hydroelectric schemes, five North West Shelf gas

production schemes or ten Adelaide-Darwin railroad schemes. Decisions

of

such magnitude should not and cannot be made without a deep and

comprehensive analytical process. Yet what we have observed with the

F-111 and JSF decisions have been essentially arbitrary recommendations

to Cabinet, justified a posteriori with an ever evolving gaggle

of 'why we had to do this' public claims.

RAAF Force Structure Planning Myths

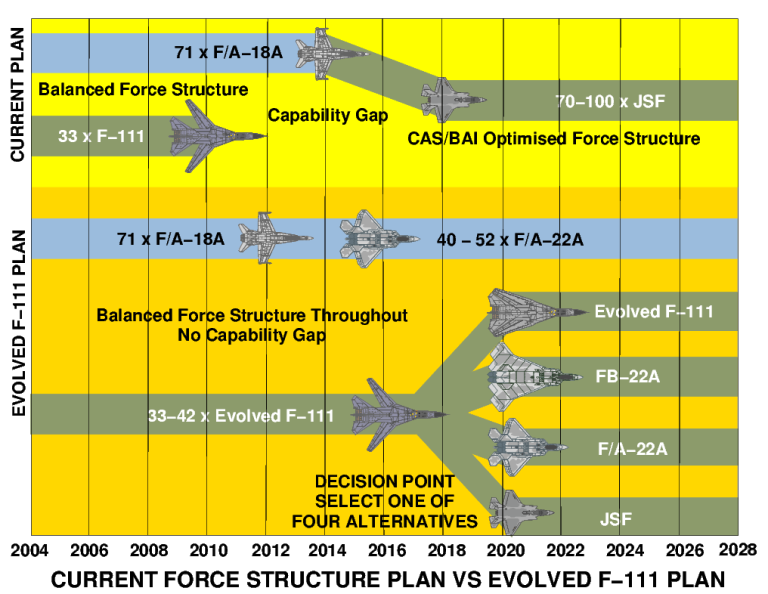

The current plan for the RAAF's future

is articulated in an Air Force submission to the JSCFADT entitled 'Air

Combat Capability' and a subsequent ASPI Strategic Insight paper by the

Chief of Air Force. This scheme envisages the effective close-down of

F-111 upgrades after the current Block C-4 Mil-Std-1760/AGM-142

upgrade,

and early retirement of the F-111 in 2010, contingent on the

introduction of A330-200 tankers and new PGMs on the F/A-18A and AP-3C

by that date. The JSF is currently the sole contender for the NACC

program, with a decision to purchase being pushed for 2006, the year

the

first JSF 'production' prototypes are to fly. While the Defence

leadership claim escape points in 2006 for the JSF decision, and 2010

for the F-111 decision, the reality is that the necessary provisions to

effect such escape manoeuvres are not being performed, making both

decisions effectively fait accompli outcomes.

In the framework of the high risk JSF

decision, the only viable long term alternatives to this aircraft are

the more capable F/A-22A, and its yet to materialise larger offspring,

the FB-22A 'regional bomber'. In practical terms, the choices for

replacing the F/A-18A with a new type distill down to the JSF or the

F/A-22A, while the F-111 could be further life extended, or replaced

with more F/A-22As, JSFs or likely FB-22As, should they materialise.

The case for purchasing the JSF over the F/A-22A as an F/A-18A

replacement has been predicated on two basic assumptions. The first is

that provision of supporting Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance

(ISR) and networking capabilities will provide a persistent assymetric

advantage over competing AWACS supported regional Su-27, Su-30 and

subsequent Flanker derivatives, which now are likely to include AL-41F

powered subtypes with supersonic cruise capability. The second

assumption is that the JSF will provide an 'F/A-22A-like' capability at

much lower cost, inside a viable timeline. Neither of these assumptions

is now intellectually supportable, nor were they supportable when the

JSF idea was hatched – they are little more than myths.

The battlefield air interdiction and

close air support optimised JSF cannot substitute for the air dominance

and deep strike optimised F/A-22A in anything but a benign environment.

In kinematic performance the JSF was optimised around the performance

envelope of the F-16C and F/A-18, aircraft the Su-27/30 was built to

kill. The F/A-22A has a sustained supersonic cruise capability, and is

built to cover the kinematic performance envelope of an afterburning

F-15 - or Su-27/30 - on dry engine thrust alone.

In stealth capabilities, the JSF is

shaped to perform best in the forward sector, and mostly in the

centimetric radar bands, to defeat battlefield air defence threats and

solo fighters. The F/A-22A was designed to defeat centrimetric and

decimetric band radars, from all aspects, this encompassing fighters,

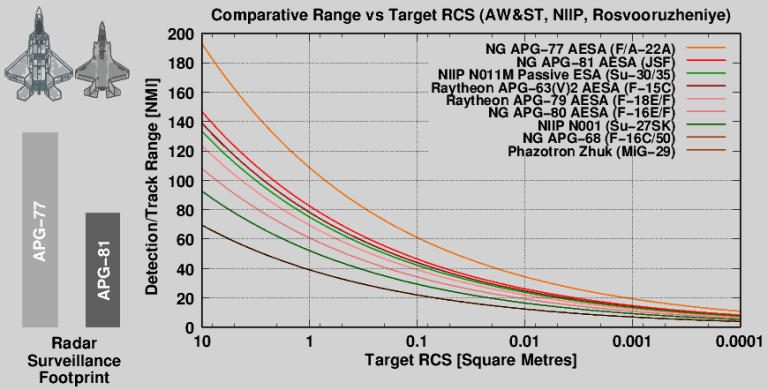

long range SAMs and AEW&C radars. The F/A-22A's large APG-77 radar

has around twice the effective coverage footprint of the strike

optimised APG-81 in the JSF.

In the strike domain, currently funded

and planned avionics and weapons for production F/A-22As cover most of

the capabilities in the JSF. While the F/A-22A is limited to the same

basic internal GBU-39/B Small Diameter Bomb payload as the JSF, but

with

twice as many air-air missiles carried, it has much greater external

payload capacity, and fuel capacity.

Available budgetary data indicates that

around 70 F/A-22A could be bought for the cost of 100 JSFs in the

timescale of interest – Defence leadership claims otherwise amount to

little more than further mythology.

The prevalence of myths and non-sequitur

reasoning observed in relation to the JSF vs F/A-22A issue, and the

networking / ISR issues, are sadly also observed in the rationale for

early F-111 retirement.

The F-111 is presented as old,

maintenance intensive, technologically obsolete, uncompetitive due to

the absence of networking, and presenting unspecified risks of age

related fleet loss.Yet there is no hard evidence to support these

arguments, and what little has been presented conflicts with hard data.

The F-111 remains a world class strike

asset, with unmatched aerodynamic performance and a very modern core

avionic system. It has range performance which permits significant

economies in tanker numbers, and the large payload and persistence

which

is vital for battlefield interdiction in a networked environment.

A good example of mythology lies in the

three alleged 'surprises' resulting in F-111 fleet groundings,

specifically leaking fuel tanks, wing fatigue related replacement and

the fuel tank wiring induced explosion in A8-112. All were byproducts

of

long known about failures in maintenance and support planning and

management, and all have since been corrected. With over 200 mothballed

AMARC F-111s to raid for structural and system components, the option

of

structural and system component replacements with new, and an ageing

aircraft engineering program in place, the F-111 could be maintained

well beyond 2020, no differently than the B-52H and B-1B, both

scheduled

for 2035+ retirement.

No less dubious is the myth that

networking equipment would be expensive to introduce in the F-111 – the

whole fleet could be fitted with JTIDS/MIDS terminals for an outlay of

the order of A$20M to 30M.

Mythology about the F-111 has not been

confined to supportability and networking alone – virtually all public

statements have avoided discussing the Mil-Std-1760 weapons capability

paid for and now being fitted in the F-111C Block 4 upgrade. With Block

C-4, virtually all of the weapons planned for the JSF and F/A-22A could

be integrated on the F-111 for the cost of software and clearances

alone.

The case for the JSF over the F/A-22A,

and the case for early F-111 retirement are not intellectually

supportable by the evidence.

Adverse Consequences of Early F-111

Retirement

If the current JSF-centric plan for the

RAAF is pursued further, and the F-111 drawdown and 2010 retirement are

implemented, the RAAF becomes exposed to some significant strategic

risks, and also loses what choices it still has today in long term

force

structure options.

The greatest risk lies in the JSF

itself, both in terms of its ability to address future capability

needs,

and in its delivery timelines and costs.

The issue of JSF capabilities, costs and

delivery timelines remains to a large extent in a state of flux, as the

aircraft has yet to transition past the 'risk hump' in development.

Until a definitive production configuration of each of the JSF variants

enters Low Rate Initial Production (LRIP) later this decade, the

aircraft's exact performance parameters and costs will remain

uncertain.

What is clear is that in 2012 we can at best expect to see expensive

early build LRIP airframes, likely requiring extensive block upgrades

later in the decade to bring them up to the then current production

configuration. Weight issues remain hotly debated in the US, especially

for the STOVL variant, which recently reverted to the smaller bomb bay

configuration originally planned for STOVL/CTOL vs the larger bomb bay

originally planned only for the CV variant.

The US Air Force recently stated its

intention to restructure its JSF buy of CTOL aircraft to a mix

including

'hundreds' of STOVL airframes, possibly with further unique design

features, to better support Army divisions with expeditionary CAS/BAI

capability. This decision will impact the cost and timelines in the JSF

program, as the USAF STOVL buy reduces the total number of CTOL JSFs

built, and pushes a larger fraction of the total build into the

timeframe of the STOVL JSF variant build. Given a fixed US Air Force

JSF

production budget, with average projected STOVL JSF flyaway cost around

30% higher than CTOL flyaway cost, the total number of JSFs built would

be reduced further increasing unit flyaway cost across all subtypes.

The combined effect of total JSF build number reduction will thus

increase JSF flyaway costs, and drive up the cost of CTOL JSFs built

early in the production cycle – exactly when the RAAF intends to buy

them.

In the simplest of terms, the LRIP CTOL

JSFs which might be available to meet the RAAF's intended 2012

introduction will be become more expensive than expected six months

ago,

further narrowing the cost gap between the F/A-22A and the JSF.

The publicly stated 'hedging strategy'

for the RAAF is to provision for centre barrel replacements of around

60% of the F/A-18A fleet, to extend their structural life. Hornet

centre-barrel replacement is a time consuming and expensive task, as

the

aircraft must be structurally pulled apart, the centre-barrel replaced

and the whole aircraft then reassembled in a jig. The whole effort can

see an F/A-18A in the depot for up to 12 months, subject to the

resourcing of the rebuild, a very different proposition from the mere

days of downtime required to swap a wing-set on the F-111. What comes

out of the F/A-18A rebuild is the same aircraft with around one sixth

of its structure zero timed, but with existing capability limitations.

Given the prospect of late running and

more expensive JSFs post 2012, the latter itself possibly impacting

delivery schedules, the RAAF faces the real likelihood of rebarrelling

a

large fraction of the F/A-18A fleet during this period, at a cost of

hundreds of millions. We thus observe a 50% order of magnitude

capability loss with F-111 retirement in 2010, followed by a period in

which a good fraction of the remaining F/A-18As are unavailable due to

rebuilds. If we measure basic force structure strength in terms of

total

uplift of a common weapon type to distance, we observe the RAAF falling

well below 40% of its current combat fleet strength. While the A330-200

tankers provide some offset in aggregate range/persistence lost, this

falls well below what is being thrown away with the F-111.

The alternative to this quagmire was

presented to Defence some years ago by Australian Industry in the

'Evolved F-111' unsolicited proposals, a model in which the F-111 was

upgraded and its service life extended past 2020 to permit acquisition

of 40 to 50 late build F/A-22As post 2012, as F/A-18A replacements,

thus

pushing F-111 replacement into the post 2020 timeframe. This model is

designed to manage and mitigate risks, spread budgetary outlays, avoid

a capability gap. Its opens up four alternative strategies for

replacing the capability in the F-111. These were further F-111 life

extension, following the B-1B/B-52H model, replacement with FB-22As, or

replacement with either more F/A-22As or JSFs, and additional tankers.

A

provision in this model was to swap 77 SQN from the F/A-18A to the

F-111F or upgraded F-111G, to spread the fatigue load accrual in the

F/A-18A fleet and extend fatigue life by around 30%. Early retirement

of

the F-111 destroys all of these alternatives, chops RAAF capability,

and drives Australia down the path of permanent capability reduction

in F/A-18A and later JSF-centric combat fleet models.

Conclusions

What we observe today in force structure

planning for the RAAF combat fleet, and its supporting rationale, is a

fundamental realignment to a force structure which priorities

battlefield air interdiction and close air support capabilities over

the long established doctrine of prioritising air superiority and

strategic strike capabilities. This unstated doctrine will expose

Australia to pressure by regional nations, and increase dependency on

US combat assets in an unprecedented fashion.

The reasoning which justifies this

change

is underpinned largely by mythology, as proper analysis was never

performed. Politically and strategically less painful alternatives

exploiting the F-111 and F/A-22A all vanish as the current JSF-centric

plan is implemented.

The future of the RAAF – and the

nation's long term strategic position in the region – will be decided

over the next eighteen months.

|

![Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433] Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433]](APA/APA-Title-Analyses.png)

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png)

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png)

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png)

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png)

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png)

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png)

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png)

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png)

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png)

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png)

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png)

![Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433] Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433]](APA/APA-Title-Analyses.png)

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png)

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png)

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png)

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png)

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png)

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png)

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png)

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png)

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png)

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png)

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png)

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png)

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png)

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png)

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png)

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png)

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png)

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png)

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png)

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png)

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png)

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png)