|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433] Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433]](APA/APA-Title-Analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Widespread

Consequences

of

Outsourcing |

|

|

Air Power Australia Analysis

2010-03

31st December, 2010 A Monograph by Air Commodore E.J. Bushell AM (Retd) Text © 2010 E. J. Bushell |

|

(Image © 1995 - 2010 Dr

Carlo Kopp)

|

|

|

|

BackgroundSince the Second World War, Australia, as well as many other Western nations, has seen major changes in its industrial base which have led in turn to major changes in management organisation and practices. To a large extent, these changes have been seen as a move from an industrial age that focussed upon manufacturing to a post-industrial age focussed upon the widespread use of technology to create modern, information-based, service industries. In concert with these changes, management organisation and practices shifted from a focus upon those technological disciplines relevant to the specification, evaluation, selection, production, operation, and support of technology to one that focussed largely upon the administrative processes involved in simply providing a service. However, difficulties encountered over the past decade or more, in industry, government and defence, have highlighted major differences between the way in which technology needs to be managed, and the manner in which it is currently administered as a service. The adverse impact of outsourcing on the skills and competencies base in technology-reliant organisations is of particular concern. Into the 1970s, management structures in technology-based organisations were typically hierarchical and forward-looking, usually providing for a planned internal succession that rested upon the corporate knowledge base – the wisdom, expertise and skills that had been built up over the years. However, this approach began to change during the 1980s, driven largely by deregulation, the need to reduce tariffs, and to improve Australia's productivity and competitiveness. The major change was to replace skilled, functional managers firstly with financial managers focussed upon short-term cost reduction, and then generalist managers, increasingly from the business management schools who usually possessed no relevant functional knowledge. (1)(2) The main tools used by 'new management' amounted to:

During the rush towards the privatisation of government enterprises and the rationalisation of industry, two damaging policies were adopted, the impacts of which remain to this day:

These changes effectively broke the chain of technological management, expertise and experience upon which both government and industry had long relied. As a result, investment in Australia's future in an increasingly technology-dependent world largely ceased. Since that time, successive governments and industries (now mostly taken over by multi-nationals) have seen in-house technical training and development as simply a cost centre that provides no ready return on investment. Both sectors have spoken loudly and often about Australia's skills crisis, but neither has been willing to face seriously the need to start reinvesting in the Nation's technological intellectual capital. Schemes come and go, at great cost, but too little, if any, effect. Stephen S. Roach pointed to the dark side of such management changes (1): “Instead of focussing on investment in innovation and human capital – the heavy lifting required to boost long-term productivity – corporate strategies have become more focussed on downsizing and compressing labor costs. The result is increasingly hollow companies that may be unable to maintain – let alone expand – market share in the rapidly growing global economy. If that's all there is to productivity recovery, the nation could well be on a path toward industrial extinction.”

That is, while downsizing and de-skilling may show short-term cost savings, it is self-defeating in the longer term as sustained productivity growth requires the very opposite – an expanding resource base of skills and competencies that keeps pace with developments in technology. Furthermore, productivity growth comes from accelerated technological innovation and a continuing improvement in the skills and competencies residing within the organisation's workforce, while downsizing and de-skilling act directly in conflict with this. Against this background, both public and business enterprises have outsourced many of their functions. While outsourcing is not new, the range of functions being outsourced has grown considerably, and there is a growing trend to outsource to overseas countries. (3) Today, experience

is

showing that outsourcing carries risks in the longer term for both

the outsourcing enterprise as well as the national good, particularly

where technology-reliant functions are involved. The widespread

consequences of outsourcing and the broad measures required to

correct them are analysed in this paper. |

|

Outsourcing Policy and PracticeBackgroundIn industry and commerce, and in government and defence organisations, outsourcing is perceived as offering:

Today, under the continued pressures of ever-shrinking budgets, and the perception that outsourcing equals productivity, outsourcing is being expanded, pushing ever deeper into organisational functions, increasing the range of perceived 'non-core' functions to the point where outsourcing frequently carries unacceptably high risks. Wide experience, as reflected in the analysis that follows, indicates that the point has been reached where the question is not whether a function is 'core' or 'non-core', but rather whether it is really 'contractable' to an outside organisation. The problems inherent in outsourcing, and the need for organisations to draw an 'outsourcing line', were analysed by Ronald Course as far back as 1930 (4). Course argued that the characteristics of the transaction can make it difficult to outsource some tasks, and in such cases an organisation would be better off to do the task itself. Tasks that are difficult or costly to outsource demand additional management and should thus be done internally, as outsourcing them and then under-managing them may well be fatal. The need to manage properly the related strategic, quantitative and qualitative risk factors associated with outsourcing was reinforced by Raiborn, Butler and Massoud in 2009. (5) The 'Course Line', that is that point beyond which outsourcing incurs unacceptably high risk to the enterprise, will, understandably, depend upon the type and level of technology central to the success of the organisation, both now and into the future. While most high technology organisations may outsource some functions, they still need to manage all or most of the tightly-integrated phases in the life cycle of the systems they operate – such as functional and technical requirement definition, project management, continuing engineering and maintenance management relative to the technology involved in terms of technical specifications, source evaluation and selection, tender and contract management, test and acceptance, and life-of-type support. These requirements hold good for both hardware and software engineering management. Outsourcing any or all of these integrated functions leaves the organisation with little or no visibility or control over such core functions as:

Tightly-integrated sub-systems and procedures underlie each of these core functions so that the operational and engineering status of a system is monitored and measured on a continuing basis, enabling risks to be identified and managed before they mature. Such considerations reinforce the old engineering precept that it is far cheaper and safer to stay out of trouble than it is to get out of trouble. Outsourcing any of these core functions breaks the functional and technical management chain, leads to loss of visibility and control, and increases functional and technical risk (3). In such cases, effective management of outsourcing will often demand as much, or more, management effort and cost as retaining it in house – that is, the 'Course Line' has been exceeded and the enterprise is at risk. In effect, outsourcing high technology tasks, on the grounds of lower cost or increased productivity, only increases the management overheads of the organisation, and if this overhead is not acknowledged and provided for with appropriately skilled resources and budgets to match, then the outsourced function will be under-managed, resulting in high risk and cost, and a further deterioration of in-house skills and competencies. Over time, outsourcing only deepens the de-skilling problems resulting from downsizing. As technology advances, the contractor benefits from the experience gained and usually retains any intellectual property – the organisation's knowledge base will thus fall further and further behind. In the end, the contractor to whom the function has been outsourced will frequently drive the enterprise through its control of the outsourced requirements. While outsourcing in-country may well result in de-skilling and further downsizing the workforce of an organisation, the skills so lost at least remain in-country as a part of the pool of national skills and competencies. However, outsourcing offshore carries the added penalty of eroding our national skills and competencies base, and may also lead to the loss of productive infrastructure. |

|

Outsourcing Information Technology SupportWhen the Federal Government announced its plans to outsource Whole of Government IT (Information Technology), The Australian Computer Society (ACS) urged caution, pointing out that “Whole of government IT outsourcing is a high risk approach for individuals, organisations and for the community as a whole. It is important that all those involved understand their obligations and the risks, as well as the potential benefits” (6). This warning was based on ACS's analytically based understanding that use of on-line technology was drifting due to a lack of direction by our politicians, media, bureaucrats and company executives, with Australian technologists hampered by a lack of vision from our technically illiterate leaders (7). ACS subsequently issued a briefing paper which highlighted: “One potential disadvantageous trade off is the existence of hidden or additional costs. One of the hidden costs in an outsourcing contract can be the erosion of staff skills. Contracts generally provide for IT staff to move to the outsourcing company, with a guaranteed period of employment. This provides a pool of staff with knowledge of the client's business and local conditions. However, over time, there may be cost pressures to use less trained and overseas staff, with a resulting lower quality of service” (8). The customer, of course, having lost his organic expertise, will generally be unable to recover the situation effectively or in a timely manner. In the US, experience with outsourcing IT shows that jobs were lost and the chain of experience that is important to technological innovation was broken and, with extensive outsourcing over time, companies lose the ability to use and develop IT innovatively. As a result, some researchers are questioning the value of broad-based outsourcing, noting that in the US banking sector the top performers were those who outsourced least. Susan Cramm also highlights the fact that leaders are built, not bought, and that building leaders requires a pipeline and a process. (9) (10). In many organisations, the IT function is critical to its existence, and is thus clearly a 'core' function that cannot be outsourced without attracting unacceptable risk. In such cases, the function should be classified and managed as 'non-contractable', and the organisation skilled accordingly. Furthermore, many organisations seem to feel that by outsourcing an IT task, they also outsource accountability for that task. In fact, accountability cannot be outsourced, much in the same way that management tasks may be delegated down the line, but accountability for that task remains with the responsible functional head. The recent Virgin Blue airline booking system 'meltdown' is a good example. Some $15 to $20 million has been reported to have been wiped from the company's pre-tax profits by the protracted failure of its outsourced computer-based booking system, although compensation may reduce this figure. Throughout the whole problem, and into the future, it will be Virgin Blue, not its IT provider, that has had to suffer the very public frustration and anger of its customers and heavy loss of revenue. In short, while tasks may be outsourced, an organisation cannot outsource its primary accountability for managing that task professionally. This incident will always be known as the 'Virgin Blue Booking System Meltdown', but it is doubtful whether the root cause will be identified and appropriate organic IT management roles and competencies introduced – legal factors and brand image will predominate. The more recent National Australia Bank IT breakdown further highlighted the widespread consequences of integrated IT system failures. The BP disaster in the Gulf of Mexico also carries many lessons for companies that are technology-dependent. No matter where the 'blame' is found finally to rest, it will always be known as 'The BP Disaster'. In this case, repeated engineering warnings of unacceptable risk were reported to have been ignored by higher management, which gives rise to the question as to whether engineering management (and BP is essentially an engineering-based organisation) carries adequate weight throughout the organisation, particularly as a check and balance where engineering problems are seen to conflict with corporate cost and schedule pressures. In 2007, following its Texas City refinery fire, the company vowed to focus 'laser-like on safety', but a month before the Gulf disaster the Occupational Health and Safety Organisation found 62 safety violations at its Ohio refinery. Now, following the Gulf disaster, the Company intends to create a safety unit that will have sweeping powers to challenge management decisions that are considered to be too risky. However, this will be to little avail if the core engineering functions within the company do not have the required skills and competencies base, together with the necessary weight and standing within the corporate organisation to balance cost and schedule pressures, for safety is fundamentally a core engineering function, not one that can be replaced by an external band aid. Safety is part of engineering! The potential for IT outsourcing to progressively de-skill organisations was discussed in an Editorial published in an Australian IT industry journal, the Open Systems Review, in 1995, which is included at Annex A. This noted that while corporate management may feel that its outsourcing decision has been a good one, it has really led to an inevitable erosion of its critical technical skills and competencies base, thus opening the corporation to increasing risk over time. The Editorial also highlighted the effects of outsourcing upon the capability of corporations to take informed technical decisions, particularly when purchasing equipment or planning computer infrastructure, noting that bad technical decisions blow deadlines, increase cost, reduce productivity and damage corporate reputation. Finally, the pervasive and growing use of IT, the rapid advances seen in IT technology and application, as well as the rapid escalation in cyber security risks, make it a function that that will have to be managed far more closely than is the case now if governments and companies are to avoid the risks associated with outsourcing core functions over which they will have little, if any, vbisibility or control (11). These organisations will need to re-skill in IT management competencies if they are to avoid the ever-spreading risk of failures of their core functions. |

|

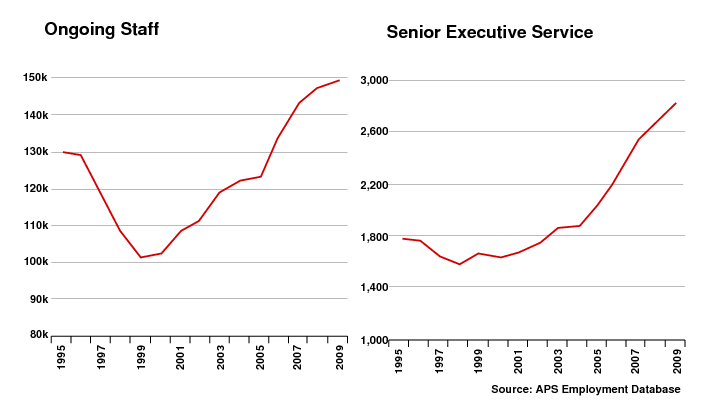

Government OutsourcingSome 45 years ago, the Vernon Inquiry into Australia's economic performance (12) lamented the poor quality of the assessment of investments in the public sector, and the resulting waste of scarce capital. The Treasury's solution was to require that public investment decisions be assessed carefully “against proper economic criteria [including] the economic return that would have been obtained had the resources been put to their most productive alternative use”. The resulting tradition of rigorous cost-benefit analysis saved many billions of dollars over the years that followed. However, today, as evidenced by the series of damning reports coming from the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) (13), the benefits stemming from the Vernon initiatives have evaporated. Governments, both State and Federal, now view rational economic assessment of their programs as a nuisance that prevents them from taking their highly announce-able and populist policy investment decisions as and when they feel that they will gain maximum political effect. Furthermore, both State and Federal tiers of government have amended their guidelines on Regulation Impact Statements (essentially cost-benefit analysis) so as to avoid public scrutiny (12). The resulting poor public decisions and lack of transparency have become toxic to both good government and good governance. Failed and deficient programs over recent years have given rise to a public perception that 'Nothing has been thought through', which is symptomatic of either a lack of the skills and competencies required to deliver sound public policy advice and provide sound policy implementation in support of government policy, or ill-advised political interference and unrealistic time frames – or both. While deregulation and productivity have been given lip service at times, there has been little, if any, policy development or action to improve Australia's current and future productivity, and greater deregulation has only resulted in more regulation. Former competition watch dog head , Alan Fels, in speaking to The Weekend Australian, argued that spending is one thing, but the growth in regulation is a more salient feature these days in most capitalist countries. “Contrary to the myth of deregulation, the amount of regulation has been rising and will continue to do so. It is a paradox. As governments privatise and try to deregulate, more regulation is required”. Within this environment, both State and Federal Public Service employment numbers over the past decade or so have grown strongly. The Federal growth is shown at Fig 1. |

|

Figure 1. APS Personnel Growth 1995 - 2009 |

|

Since

1998, the Senior

Executive Service (SES) grew by 81% compared with 38% for the entire

public service. However, while some 40% of federal ongoing staff are

located in Canberra, some 75% of SES staff are based in the Capital,

essentially in ministerial offices and executive suites of

departmental buildings (14). Despite this marked growth in senior

executive staff, the Federal Government has turned to management

consultants, academics, market researchers, think-tanks, and the help

of media advisers, to fill perceived gaps in policy development

advice that the bureaucracy has been unable to satisfy. Bureaucracies

have also outsourced many of their own core tasks, some

to the point where they have, at the executive level, now become

highly paid but unproductive overhead. This complex, dysfunctional

and expensive structure is symptomatic of:

This has led to a growth in administrative process in an effort to fill the vacuum created by the paucity in specialist departmental skills and competencies, and the imposition of administrative process under compliant 'managers' (replacing management by experts), at functional organisations, such as schools and universities, hospitals, and infrastructure projects, to name only a few.

As a result, departments are incapable of undertaking their delegated responsibilities competently, in a timely fashion, or economically, and, thus, are unable to manage outsourced tasks competently. While governance mechanisms have frequently identified these problems, meaningful corrective action has been avoided by successive governments. Accountability for the debacles that have occurred has also been largely avoided. While the Minister carries primary responsibility for his department, it is the Secretary who carries responsibility for the proper administration and competent management of the functions performed within the department. However, Secretaries, who are now seen as equivalent to Chief Executive Officers in industry, are invisible and seem unburdened by any accountability as would happen in industry. Finally, in

contrast

with the organisational flattening, downsizing and deskilling that

took place within industry, there has been strong growth in the

Federal Public Service, particularly in the SES Bands, which should

have led to an improvement in the management of government business,

including the identification and management of tasks that should and

those that should not be outsourced. If improved government competence is to be achieved, as it must, government departments and those who staff them will need to develop and regain those specialist skills required for the proper discharge of their responsibilities. In the main, these will relate to technology and basic task management competencies. The critical need to re-skill the Public Sector, and redress the centralisation of power within Ministers' offices, should rank as two of the most important areas for evaluation and action by those in government responsible for ensuring good governance. Finally, functional organisations must be freed to manage their affairs in a professional manner as they are far better able to determine the resources needed and how they should be spent. |

|

Reform of the Public ServiceIn September 2009, the Prime Minister established an Advisory Group to review Australian Government administration and to develop a blueprint for reform. The report and blueprint were delivered in March 2010 (15).While the group raised the question as to “How is the APS performing?”, its report fails to look seriously at, let alone answer, that question, and simply goes on to say that a world-class public service must:

In the absence of any qualification or quantification of problems (perceived or otherwise) and their solutions, the report claims “That the blueprint recommends nine signature reforms grouped under the core components of high performance” in order to achieve “A high performing public service”. The nine signature reforms, not surprisingly, all lack characteristics that could be referred to, even remotely, as substantive. The Forward to the report finishes with: “More broadly, the Blueprint puts people at the centre of public service reform. Ultimately, it is people, not systems, who produce excellence and drive change”. The report thus follows in the tradition of previous such reports, controlled by an APS comprising people who simply follow administrative process, rather than an organisation striving to achieve outcomes – an organisation which follows a systems approach requiring the disciplined and auditable application of real, demonstrable skills and competencies, in accordance with appropriate and sound management policies, systems and procedures, to achieve a planned outcome. In summary, the report and its blueprint fail as an incisive, robust management analysis of the need for improved APS performance and how real change might be made. In implementation, its proposals will be costly and time consuming, and will most likely result only in a call for more staff to handle the additional reviews and complex processes introduced, leaving the underlying causes untouched. Subsequent to the report, Terry Moran, Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, in his speech to the Institute of Public Administration on 8th December 2010, stated that, while the Federal Public Service is there to serve the PM and Cabinet, its higher goal was serving the nation's citizens, putting their needs, individually and collectively, at the centre of its work. While acknowledging that the public service is obsessed with administrative process at the expense of outcomes, he wants public servants “to explore new ideas to find new ways of delivering services and tackling problems...to encourage new ways of asking questions”, and to seek agility, vision and a sense of vocation. Fine and lofty words, but the report, despite input from the seven First Assistant Secretaries who form the 'in-house' management consultancy established within Mr Moran's Department, provides little of substance as to how his words will be made to produce the effective, timely and economic outcomes he seeks. For example, the steps then outlined by the Secretary to improve public service efficiency amounted to:

Unfortunately, all avoid the three keys to a better performing public service:

Feed-back loops, integrated with, but independent of, functional management, are designed to provide current and accurate project status visibility up through the executive chains of management and governance. Such feed-back loops, properly resourced in skills and competencies, offer a more cost effective and time efficient means of introducing reforms that become self-actualising and so will not fade over time or through interference or neglect or the pursuit of self advantage. Such loops may be expected to be formed and functioning within about twelve months and be achieving self-actualising behaviour within two years. Using such an approach, the complexities seen within a public service overly focussed upon process rather than managing outcomes are not a bar to real and timely reform. |

|

Outsourcing Defence CapabilitiesThe rush to flattened organisations, de-skilling and outsourcing also swept through Australia's Defence Organisation (ADO). Traditionally, the Services possessed and developed the core operational, management, and engineering skills and competencies base required for mounting, sustaining and supporting operations, as well as those for specifying, evaluating, selecting, procuring, introducing and supporting/sustaining new capabilities. The over-arching policies, systems and procedures employed had been built up over decades of hard-won experience.However, this competent and widely-respected organisation was swept aside by the structural changes that started with the Tange Review of 1974, followed by the Commercial Support Program (CSP) (1991-97) and the Defence Efficiency Review (DER)/Defence Reform Program (DRP) from 1997. These led, for example, in the highest technology Service, the RAAF, to:

The structure evolved by Defence to replace the lost core Service functions in capability definition, acquisition, and sustainment has become the Defence Materiel Office (DMO), a wholly centralised organisation characterised by a contract-centric, quasi- business-like management approach that sees operational analysis, project management, risk management and engineering skills and competencies as contract-supporting services, not contract drivers. From its earliest days, DMO has failed to understand risk management, which has led to its acceptance of exceptionally large risks and its adoption of two ingrained outsourcing practices:

Despite being advised repeatedly that capability definition, acquisition and sustainment must be driven by a tightly-integrated flow of operations analysis, robust project management, and strong engineering expertise in the technology being acquired, and that current outsourcing practices carry long-term cost and national security risks, nothing has changed for the better. Defence/DMO's response to perceived problems has been to add additional layers of process and raise the level of bureaucratic overview which, by its nature, leads to obfuscation and a lack of clear task accountability. The problems that DMO has encountered with the management of its major projects were highlighted in the critical ANAO report into DMO Major Projects for 2008-09, which was analysed in detail in the report cited at (16). It is thus not surprising, that after a decade or more, DMO Major Projects are still being characterised by such basic problems as those listed in the recent ANAO Lightweight Torpedo Replacement Project Report (17):

Assessed against the key purpose of a major capital acquisition, the ANAO report judged that the project has not been managed effectively as it will not deliver the capability originally sought by the ADF and, although the project remains within budget, this has been achieved by removing three of the five platforms to which the torpedo was to be fitted. Each of these difficulties is symptomatic of:

DMO is thus a good case study of the failure of 'new age' flattened, downsized, and de-skilled organisations, that rely upon the outsourcing of functions that are inherently not 'contractable'. In the face of continued failures and deficiencies in the management of capability requirements, “The Defence Capability Handbook 2010, which was released in interim form in March 2010, indicates that military or commercial off-the-shelf options should be used as a benchmark for considering acquisition options. The handbook indicates that any option that moves beyond the requirements of an off-the-shelf solution must include a rigorous cost-benefit analysis of the additional capability sought so that the full resource risks and other impacts are understood” (18). In short, Defence/DMO are abandoning their core responsibility for ensuring that Australia's military capability requirements are identified properly and satisfied in light of Australia's unique needs and operating environment. Mandating off-the-shelf solutions merely takes pressure off Defence/DMO bureaucrats on the pretext of saving time and money, but it carries a real danger that Australia's military will become further de-valued in core skills and competencies, and only equipped to fight someone else's threat systems in someone else's threat environment and geography. |

|

The Way ForwardRedressing the widespread problems stemming from outsourcing will require positive action to be taken in several areas of both business and government management. The task will be neither simple nor easy, but action must be taken if Australia is to regain its reputation as a 'smart' nation, one able to manage effectively both current and evolving challenges in a technology-intensive environment. Primary responsibility must rest with government to re-skill the Public Sector and redress the centralisation of power in Ministerial offices, as well as set the policy framework, restructure, and resource our education and training systems at all levels. Quality and substance must be the key drivers rather than lowering the bar to produce increasing numbers of ill-prepared graduates at a perceived lowest cost. In particular, government needs to recognise that the customers of our education systems are primarily industry, commerce, business and government enterprises - those who create and manage our wealth. All rely upon our education system to deliver the products they require – the skills and competencies needed to remain efficient and competitive over time, while advancing our national intellectual capital. Some established concepts and practices will need to change. The customer is not the student, and the education system is not simply a lowest-cost, 'service provider', as is the case now. This path has lead only to progressive lowering of standards and the devaluation of our whole education system and national reputation, resulting in gross inadequacies in the national skills and competencies base (19) (20). Enterprises, for their part, and particularly those that are technology-reliant, need to better identify their 'core' and 'non-contractable' functions, and develop and maintain the technical skills and competencies base needed for their professional management. They must also ensure that these functions are given the importance they deserve and take their proper role and place in the management structure. Finally, sound management principles and practices need to be ingrained at all levels, as these are the foundations upon which all other competencies are built. |

|

ConclusionsSince the 1980s, Australia's industrial base has undergone major structural and management changes. Functional structures were flattened, downsized and de-skilled in the search for increased productivity and competitiveness. In technology-reliant enterprises, these changes resulted in a change in focus from the long-term management of the technology upon which the enterprise depended to a short-term focus upon reducing costs in all functional areas, with engineering disciplines being viewed merely as separate cost centres, and their functions as service providers able to be outsourced. As part of these changes, outsourcing perceived 'non-core' functions has become increasingly common. However, outsourcing tasks, particularly in technology-reliant enterprises, directly increases management overheads which, if not recognised and provided for, will result in the outsourced task being under-managed, leaving the enterprise open to high risk and cost. Over time, outsourcing only deepens the de-skilling embedded by downsizing. Outsourcing overseas carries the added penalty of eroding our national skills, national wealth and competencies base, and often leads to the loss of productive infrastructure. The outsourcing of IT functions carries the potential to progressively de-skill IT-dependent organisations so that they soon become unable to take informed technical decisions when specifying their IT requirements, select and purchase equipment, or plan their computer infrastructure. The result has often been bad technical decisions, blown deadlines, increased cost, reduced productivity and damaged corporate image. With rapid advances in IT technologies and applications, as well as cyber threats, current problems will only escalate. IT-dependent organisations must thus re-invest in organic IT skills and competencies if they are to survive. Experience with government outsourcing reveals similar problems, but within a far more self complicated and politically charged management environment than private organisations. The general problem that has developed in the public sector has been the concentration of non-skilled advisors in ministerial offices and similarly un-skilled executives in senior departmental positions, particularly at the federal level, together with the politicisation, fragmentation, and blurring of accountability throughout the administration. This has upset the important balance that once existed between politics and what should be a politics-free administration that implements government policies and programmes effectively, efficiently, timely, and economically. Within this environment, the proper management of projects, including outsourcing, has become almost impossible. Government is also the main provider, through our training and education systems, of the skills and competencies base that Australia needs if it is to remain competitive in a rapidly changing world – an area where sweeping improvements are sorely needed. Within government, the complexities seen with a public service overly-focussed upon administrative process rather than the management and achievement of outcomes, and being resistant to change, are not a bar to real and timely reform if the approaches to management outlined herein are adopted and feed-back loops are employed. DMO is a good case study of the failure of 'new age' flattened, downsized, and de-skilled organisations that now rely upon the outsourcing of functions that are inherently 'not contractable'. The difficulties that DMO still faces after more than a decade may be traced directly to:

Redressing the adverse effects arising from the misapplication of outsourcing need not be complicated, and must be done if Australia is to again become a 'smart' nation with the skills and competencies base required now and into the future. Government must restructure and resource our education and training systems to inject quality over quantity, while enterprises must revalue technological skills and competencies and ensure that the roles and importance of engineering management are recognised and reflected within their management structures. Finally, sound management principles and practice need to be ingrained at all levels as these form the foundations upon which all other competencies rest. |

|

Endnotes/References |

|

1 Roach, Stephen S, URI: http://hbr.harvardbusiness.org/search/Stephen+S+Roach/o/author. Stephen Roach has written on the critical distinction between efficiency and productivity. He also emphasises the importance of educational attainment as a good measure of the return on investment on human capital, and points to the decaying standards in the US, a trend also noticed in Australia. 2 Over recent years, the role and performance of Master of Business Administration (MBA) graduates have come under scrutiny. However, it should be recalled that MBA schools were originally established some 60 years ago by Harvard University to give engineers management training so that they could more easily move into senior executive positions. Since then, rules for admission to MBA courses have been relaxed to the extent that students with almost no management experience, let alone engineering qualifications, are routinely admitted. The result has been to graduate MBAs who lack any solid skills base. In short, management training is important, but it has to be built on a solid skills base. 3 Grove, Andy. How America Can Create Jobs, Bloomberg Business Week, 1st July 2010; Grove, an ex CEO and currently Senior Advisor, Intel, highlights the full effects of outsourcing overseas on jobs, loss of technology know-how, breaking the chains of experience, and the organic and innovative evolution of technology. 4 Course, Ronald, who won the 1991 Nobel Prize in Economics for his theory on 'core', 'non-core' and 'contractable' outsourcing in terms of the 'transaction costs' involved. Course sees the term 'outsourcing' as being misleading, as every outsourced task is accompanied by the responsibility to manage that task properly. The responsibility for a task may thus be moved to an outside contractor, but primary accountability for the task and its quality must always remain with the outsourcing enterprise. 5 Cecily A. Raiborn, Janet B. Butler, Marc F. Massoud, Outsourcing Support Functions: Identifying the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Discusses the need to manage the related strategic, quantitative and qualitative risk factors associated with outsourcing. Product #BH337-PDF-ENG, 15 July 2009. 6 Australian Computing Society (ACS) Media Release, ACS Urges Caution on Whole of Government IT Outsourcing, 11th July 1997. URI:http://www.acs.org.au/president/1997/outsrc/paper.htm 7 ACS Presentation for the National Press Club, Australia's 'Net Futures, 11th December 1996. 8 ACS Paper, Outsourcing and Contracting Out IT Products and Services, 6th August 1997. URI: http://next.eller.arizona.edu/courses/outsourcing/Spring2005/student_papers/final_pape/final%20paper1raeef.doc. 9 Cramm, Susan D., Does Outsourcing Destroy IT Innovation?, URI: http://blogs.hbr.org/hbr/cramm, 28th July 2010. Cramm looks at problems developing IT leaders in an outsourcing environment and identifies six problems (common to most technology-dependent organisations) that arise from inadequate organic expertise and experience. 10 Cramm, Susan D., Where Are Tomorrow's IT Leaders?. URI: http://blogs.hbr.org/hbr/cramm/2010/08, 9th August 2010. Expands upon 9. 11 Software programming, data entry, processing and storage for major corporations are now done routinely by overseas contractors. 'Cloud computing' is an extension of this trend, driven by an increasing demand for speed and volume. While such technological developments may seem irresistibly attractive, they carry major challenges to the outsourcing enterprise in stating their management requirements and assessing the risks involved in managing the outsourced task. 'Cloud computing' is where the computing function itself is delegated to a large number of servers owned by a small number of global vendors. URI:http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2009/08/outsourcing_where_will_you_dra.html 12 URI: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/opinion/more-dodging-of-cost-benefit-tests/story-e6frg6zo-1225928592812. 13 Recent Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) Reports highlighting the difficulties being encountered in managing outsourced functions by government include: ANAO Performance Audit Report No 8 – Multifunctional Aboriginal Children's Services (MACS) and Creches,23 September 2010. ANAO Performance Audit Report No 9 – Green Loans Program, 29 September 2010. ANAO Performance Audit Report No 11 – Direct Source Procurement, 30 September 2010. ANAO Performance Audit Report No 12 – Home Insulation Program, 15 October 2010. 14 URI: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/politics/monster-we-could-not-tame/story-e6frgczf-1225809427399. 15 Ahead of the Game – Blueprint for the Reform of Australian Government Administration, March 2010, The Advisory Group on Reform of Australian Government Administration. 16 ANAO Report on Defence Defence Materiel Office (DMO) Major Projects Report (MPR) 2008-09, and the Transcript, Joint Committee, Public Accounts and Audit (JPCAA) Hearing on DMO MPR 2008-09, Submission No 1. These provide a detailed analysis of the 15 major projects subject to the report and the hearing and highlight the matters raised herein. 17 ANAO Report No 37, 2008-09 – Lightweight Torpedo Replacement Project Report. This is one of many covering specific DMO major projects. 18 URI: http://www.defence.gov.au/dmo/id/dcp/html/index.html. 19 De Percy M., How to Rank the Quality of Education?, The Drum, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 20th July 2009, URI: http://www.abc.net.au/unleashed/28674.html. 20 Kopp C. Fixing the National Skills Shortage, Defence Today, June 2009. |

|

Annex A: Deskilling - Can We Afford It?(Kopp C., Commentary [Editorial], Open Systems Review, February 1995.) One of the most disturbing trends which we are seeing in today's industry is deskilling. Whilst this trend is broader than the computer industry alone, affecting all industries which rely on technology as a component of their operational environment, the computer industry by its very nature is more vulnerable to its longer term effects. The central argument in a deskilling process in a typical organisation is that off-the-shelf software and hardware products, shrinkwrapped products, are now good enough to be productively used by staff of a relatively lower standard of education and experience, than would have been required a half a decade ago. Replacing an expensive staff member with a cheap staff member and a shrinkwrapped product results in a substantial reduction in costs, particularly ongoing payroll costs. This constitutes a demonstrable gain to the organisation's balance sheet. Or does it? Are shrinkwrapped products, canned technology, and low skill staff really more cost effective than high skill staff and customised solutions? Are we gaining by displacing troublesome 'technology for the sake of technology' techheads with compliant junior staff or laymen? The answer is in most instances, no. While the payroll costs may somewhat diminish, the nett costs may in fact increase. Lower skilled staff will require more training, more supervision and will usually not match the productivity of an experienced programmer, systems administrator or engineer. The issue of shrinkwrapped technology vs integrate yourself technology is closely related. How many readers can honestly say that the canned solution performs that much better than the previous solution integrated in-house? How many hours are spent on the telephone attempting to extract support time from a supplier? Does the cost of support contracts really balance the savings, if any exist, in staff salaries? When things go wrong, can the less experienced staff improvise successfully? These are items that are easy to quantify, and visible in the short term. There are other hidden factors, which can insidiously reduce an organisation's profitability, and these are not always obvious in the shorter term. The most interesting of these is the effect upon the capability to make informed technical decisions, particularly when purchasing equipment or planning computing infrastructure. The Open Systems market is in many ways a technological jungle, where only the fittest survive. This true of vendors as well as users. Bad technical decisions blow deadlines, increase costs, reduce productivity and damage political credibility within organisations. There is no substitute for technical insight and experience. Living in an Open System market means living and dying by the quality of your decisions, and the quality of a decision to acquire equipment x, facility y or service z determines whether the exercise is a success or a disaster area. Doing things successfully means understanding the technology and its longer term implications, having the ability to identify real technological trends and being able to extract facts from the deluge of buzzwords. An organisation which has succeeded in its deskilling strategy will achieve a number of things:

Can we really afford to deskill? |

|

|

Air Power Australia Analyses ISSN 1832-2433 |

|

|

|||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

|||||||||||||

| Artwork, graphic design, layout and text © 2004 - 2014 Carlo Kopp; Text © 2004 - 2014 Peter Goon; All rights reserved. Recommended browsers. Contact webmaster. Site navigation hints. Current hot topics. | |||||||||||||

|

Site Update

Status:

$Revision: 1.753 $

Site History: Notices

and

Updates / NLA Pandora Archive

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Tweet | Follow @APA_Updates | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||