|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-NOTAM.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-NOTAM.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

United Kingdom: F-35 or F-22?

|

||||||||

|

Air Power

Australia - Australia's Independent Defence Think Tank

|

||||||||

| Air Power Australia NOTAM 25th February, 2009 |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

As the unit procurement costs of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter progressively converge with the unit costs of the F-22A Raptor, and the F-35 becomes progressively less survivable as threats evolve, it is time for the UK to cut its losses, bail out of the JSF program, and opt for the F-22A instead. A US Air Force study published in 2000 identified Britain as one of three allies who could be supplied the F-22 without any risk of technology leakage (Author). |

||||||||

|

The

F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter is designed to defeat threats

that will have been superceded well before this aircraft enters

operational service. The performance of the F-35 is suffering seriously

from the conflicting design requirements that it was intended to meet.

As a result, the F-35 is shaping up to be a technological failure, a

delivery schedule and 'affordability' failure, and a techno-strategic

failure. This will place Britain in the position of having to

look at replacement options, which are extremely limited in view of

developing threat capabilities. The question that must inevitably arise

is: 'Should Britain Ask the United States for the F-22?' Britain remains the largest single

overseas partner in

the F-35 program, and as this program unravels, Britain stands to lose

much more than the other partner nations in a sunk investment not

producing

any direct return, and in political

embarrassment. From a political perspective, America needs to start

thinking

about what alternatives it can offer the British as credible

substitutes for

the uncompetitive and technically troubled F-35. The F-16E, F/A-18E/F

and

F-15E/SG do not qualify as credible substitutes given the proliferation

of high

technology Russian designed Flanker fighters and double digit SAMs on

the

global stage. None of these types can survive in such an environment. Britain’s intent to procure the

expensive and

underperforming F-35 for the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy has

produced

intensive domestic criticism, some well

informed and

technically correct, some less so. What is clear however is that

Britain does

need new technology fighters to replace a range of increasingly less

viable

legacy aircraft, as well as the Royal Navy’s now retired Sea Harriers. About a decade ago the F-22A Raptor was

proposed as an

alternative to the domestically built Eurofighter Typhoon. Britain’s

influential aerospace industry lobby killed that proposal, rubbishing

the F-22

with some very dubious DERA JOUST simulations, which claimed the “Typhoon

was 81

percent as good as an F-22”. Forensic analysis showed this

was

nonsense,

an assessment since

then borne out by the operational experience of the US Air Force flying

the

F-22 against a range of conventional fighters. Current planning for the Royal Air Force

and Royal

Navy is to procure the F-35B STOVL JSF as a replacement for the RAF

Harrier

GR.7/9 fleet, the Jaguar GR.3, retired in 2007, and the Royal Navy Sea

Harrier

FA.2, retired in 2006. Cited numbers vary between 150 and 138 aircraft,

although reports emerging from the UK late last year suggested a

reduction to

as few as 85 aircraft. This is a

far cry from the euphoric speculation of early 2002, when senior RAF

staff

officers privately suggested to their Canberra colleagues that the RAF

should

be replacing its remaining Panavia Tornado GR.4s, Tornado F.3s, and

earlier

built Typhoons, with the F-35A JSF. Over the next two decades Britain will

need to replace

most if not all of its combat aircraft with credible new technology

replacements. The only new fighter in the UK inventory is the Typhoon

F.2, which

is technologically comparable to currently built American F-15 and

F/A-18E/F

fighters. While more agile than these legacy US fighters, it is equally

vulnerable to advanced SA-20/21/23 Surface to Air Missile systems, and

new

generation Su-35BM class Flanker variants. The new ramjet MBDA Meteor

Air to

Air Missile may eventually provide a credible capability against older

Flanker

variants, but will be matched over the next decade by the Russian

ramjet Vympel RVV-AE-PD missile. The

Typhoon has been justifiably

criticised for program procurement costs which have been similar in

magnitude to

the vastly better F-22 Raptor. |

||||||||

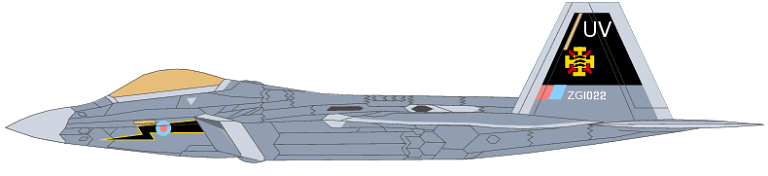

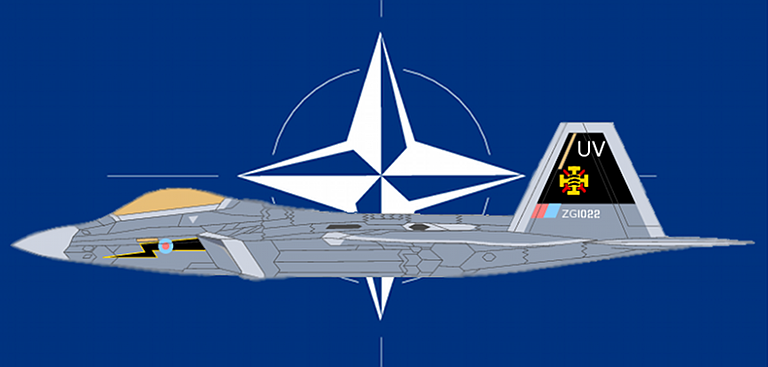

The

Royal

Air

Force will need replacements for the Tornado IDS (above) and

Tornado ADV (below), capable of penetrating advanced air defences and

defeating Su-35BM class fighters. The F-22A can perform both roles

better than any other design planned or in service (RAF image).

The Typhoon F.2 is one of the most

expensive fighters ever built, but lacks the stealth to penetrate

modern SAM defences, and the persistence to compete with the latest

Su-35BM class Flanker variants (MBDA image).

The F-35B is intended to replace the Harrier GR.9 (below) and already retired Sea Harrier FA.2 (above). With Britain's planned new carriers to be much larger than the Invincible class, and the ubiquity of modern Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance systems rendering dispersed basing almost irrelevant, there is not a compelling case for a STOVL aircraft to replace the Harrier variants (Royal Navy images).  |

||||||||

|

Britain’s long term strategic needs have

been the

focus of much of the criticism directed at re-equipment plans for the

UK

fighter fleet. Sadly much of this criticism has been myopic,

concentrated on

short term considerations relating to Counter INsurgency Operations

(COIN) in

the Islamic world. In this respect Britain has suffered from the same

nonsensical very short term argument seen in the United States, and

Australia. There is little doubt that over the long

term Britain

will need to provide some credible expeditionary capabilities to

support

coalition operations on the global stage. While another Falklands

scenario is

unlikely, given the loss of Britain’s overseas colonies, the need to

intervene

globally is unlikely to vanish. If future UK governments intend to

contribute

capabilities of any real use, they will need systems which are

effective and

survivable against the modern Russian high technology systems

proliferating

globally, and also interoperable with other coalition assets. Systems

which soak up US forces as protective escorts to stay

alive

are more of a hindrance in a coalition campaign, than a contribution of

value. What should be of more concern to

Britons are the

increasingly toxic relationships between Putin’s Russia and the many

former

Soviet Republics, and former Warsaw Pact allies in Eastern Europe.

Putin’s

confrontational and coercive foreign policy and military interventions

along

Russia’s exposed Western and South Western borders have fuelled

mistrust and

resentment in nations which were already largely resentful over Soviet

era

misdeeds. The expansion of NATO eastward has been a by-product of this

progressive breakdown – not vice versa as is often claimed. Russians

feel

exposed without hundreds of kilometre deep buffer territories and this

perceived vulnerability with its resulting fears

will not disappear any time soon. While Putin’s Russia will never be

another Soviet

Union, Russia is slowly recapitalising its Cold War era military with

advanced

systems, and will have a genuine capability to project coercive air

power

against European NATO nations. If any of the myriad ongoing disputes

between

Russia and its now NATO aligned neighbours degrade into shooting

conflicts,

the

Russians will be able to drop smart bombs across much of Eastern

Europe, unless

the US Air Force deploys most if not all of its F-22 Raptors into

European NATO

airfields. Moreover, as Russia builds up numbers of the SA-21, it will

be able

to declare and effectively enforce permanent air exclusion zones up to

200

nautical miles outside its geographical borders – a

Surface-to-Air-Missile-based buffer zone that would appeal to Russian

fears of

being subjected to attack by cruise missiles and conventional aircraft. European NATO nations can look forward

to the prospect

of Moscow not only turning off the gas supply, but also exercising

military

muscle in NATO’s backyard. The expectation that the Americans will

permanently

commit their already overcommitted future F-22 fleet to cover for

European

military underinvestment is clearly asking a little too much and, at

best, fanciful thinking. It is worth observing that the character

of developing

Russian capabilities is very different from the Cold War era Soviet

model.

Rather than the vast numbers of mostly unsophisticated shorter ranging

dumb bomb

armed tactical fighters the Soviets deployed, Russia is emulating the

US model

of smaller numbers of highly sophisticated high technology long range

aircraft

armed with

precision smart weapons. Large numbers of low performance fighters,

including

the F-35, are virtually useless against Russia’s new generation Su-34

and

Su-35BM fighters. While the broader issues of European

NATO security are

bigger than Britain’s needs alone, they underscore the realities of an

uncertain future in a complex multipolar world. Technological

evolution and poorly thought out specification/definition of the F-35

design

has seen to it that by the time the F-35 would deploy, assuming it

survives its

engineering, cost and schedule problems, the F-35 will be wholly

uncompetitive

against the new generation of Russian designed weapons. That margin

will grow

as Russian and Chinese weapons evolve over the next three decades,

while the

overweight, underpowered, over-packed and under-stealthed F-35’s built

in

design limits make it increasingly outmatched. Whether Britain wishes to conduct

expeditionary

warfare in coalition or unilaterally, or participate in European NATO

continental defence, its Eurofighter Typhoons and planned F-35 JSFs

will likely

be fodder for the latest Russian weapons, unless the opposing side is

an

undeveloped Third World nation. The prospect of Russian contractor

(i.e.

mercenary) aircrew, ground-crew and missileers being deployed to Third

World

nations with the available cash introduces uncertainties even in the

latter

circumstance. It has happened before. The wisest strategy for the United

Kingdom is to

negotiate access to the F-22A Raptor and bail out of the F-35 program

at the

earliest. An even wiser strategy is to collaborate with the Americans

on the

development of a navalised F/A-22N Sea Raptor, to drive down costs for

the US

Navy, Marine Corps and Royal Navy. The uncompetitive Typhoon can be

relegated

to air defence of the British Isles, and F-22A and F/A-22N used for

expeditionary warfare and NATO air defence commitments on the continent. While much has been said and written

about not

exporting the F-22 to US allies, what is less well known is that two

studies

have been done to determine exportability of the F-22. The first of these is the public

unclassified

geostrategic and political assessment performed by then LtCol Matthew

Molloy,

USAF, who produced a 98 page study while posted to the Maxwell AFB School of

Advanced Air Power Studies of the Air University, in 1999-2000. This

document

identifies Australia, Britain and Canada as the three US allies who can

be

trusted without question to operate the F-22 and protect its technology

[1]. Less well known is a more detailed and

not publicly

released study performed by the US Air Force during the same period,

often

known as the “anti-tamper study”, which looked at risks arising from

downed

aircraft scenarios. The study also assessed the risks arising in

exporting the

aircraft to close allies, specifically Australia, which was known to

have a

developing strategic need for the F-22. The study concluded that it was

safe to

supply the very same configuration of the F-22 flown by the US Air

Force to

Australia, as the risks of unwanted technology disclosure were no

different to

those expected for the US Air Force. Considering both the Molloy study and

the

“anti-tamper” study, the notion that the Americans would not export

some

configuration of the F-22 to the United Kingdom is difficult to accept. The problems, which the Britons must

confront at a

strategic level arising from Russia’s devolving relationships with its

neighbours, and the ongoing demand for global intervention forces, are

problems

to a greater or lesser degree shared by other leading European NATO

nations.

The difficulties arising from involvement in the ill considered F-35

program

are also shared by a number of other European

NATO

nations, as well as the United Kingdom. The unavoidable strategic reality is the

European NATO

nations will need a credible capability to discourage adventurous

future

Russian behaviour in Eastern Europe, and to make a useful difference in

expeditionary warfare. None of the indigenous European fighters, or

the F-35,

will be particularly useful in either kind of contingency. Two to three

full

strength Fighter Wings comprising 50 to 70 F-22 Raptors each would

provide

enough deterrent capability and sustainable / survivable firepower to

address

Europe’s needs for decades to come. While the NATO AWACS fleet model of a

shared resource

would be a politically attractive way for Europe to deploy an export

configuration of the F-22, it would present practical operational

problems. The United States needs to think long

and hard about

how to redress Europe’s worsening strategic weakness, as it has the

potential

to soak up disproportionate US military resources in any serious

contingency.

Exporting a variant of the F-22 rather than the uncompetitive F-35

would solve

much of that problem. With the long term future of the F-22

now the subject

of intensive political, public and analytical community debate in

America, and

the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter now showing the symptoms of an incipient

technological “death spiral”, the time is right for the Obama

Administration

and H.M. Government to jointly explore the export of F-22 Raptor

variants for

the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy, as an “escape strategy” from the

F-35

program.

There is a good precedent: when it became clear that the Nimrod AEW.3 could not be made to work in a reasonable timescale and cost, H.M. Government cut its losses, dumped the program and promptly acquired the top tier Boeing E-3D AWACS instead. The basic strategic challenges both America and Britain face are much the same, whether we consider European NATO contingencies, or expeditionary warfare. The Alliance relationship is as close as it has ever been. All that is needed is the political courage and strategic foresight to make a break from the past, well intentioned but fundamentally flawed, choice of the F-35. |

||||||||

Endnotes:[1] Matthew H. Molloy, Lt Col, USAF , U.S. MILITARY

AIRCRAFT FOR SALE: CRAFTING AN F-22 EXPORT POLICY, SCHOOL OF

ADVANCED AIRPOWER STUDIES ,

AIR UNIVERSITY, MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE, ALABAMA, JUNE 2000, URL: https://research.maxwell.af.mil/papers/ay2000/saas/molloy.pdf.

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Air

Power

Australia Website - http://www.ausairpower.net/ Air Power Australia Research and Analysis - http://www.ausairpower.net/research.html |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| |

||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

|||||||||||||

| Artwork, graphic design, layout and text © 2004 - 2014 Carlo Kopp; Text © 2004 - 2014 Peter Goon; All rights reserved. Recommended browsers. Contact webmaster. Site navigation hints. Current hot topics. | |||||||||||||

|

Site Update

Status:

$Revision: 1.753 $

Site History: Notices

and

Updates / NLA Pandora Archive

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Tweet | Follow @APA_Updates | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||