|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-Main.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-Main.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lockheed-Martin

F-35 Joint Strike Fighter |

Dr Carlo Kopp, MAIAA, MIEEE, PEng First published in Australian Aviation April/May 2002 |

|

Part 1 A Cold War Anachronism?

Judging from the media rhetoric in early January this year, one could almost be forgiven for believing that the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) was the anointed replacement for Australia's F/A-18A and F-111 fleets - no doubt to the annoyance of many in Defence who are immersed in the complexities of AIR 6000 capabilities definition. The reality of the Joint Strike Fighter is much less sparkling as many would like us to believe. In this month's analysis we will explore some of the issues. The new LM F-35 Joint Strike Fighter has the distinction of being a first in more than one respect. It is the first combat aircraft to leverage the massive US Air Force research & development investment in the F-22 family of aircraft. It is also the first attempt since the 1960s TFX (F-111) program failure to produce a fighter which can meet the needs of all three US services with fighter fleets, as well as the needs of export clients. As the Joint Strike Fighter program includes both conventional, carrier capable and STOVL variants, it is the first ever attempt to create a fighter which spans three very distinct deployment regimes. Finally, it is the first attempt to produce a very low cost aircraft with genuine stealth characteristics. With the prospect of around 3,000 Joint Strike Fighters for the US services, replacing the F-16A-D, A-10A, F/A-18A-D and AV-8B, and the potential to render all European fighter offerings wholly uncompetitive in the large F-16 and F/A-18 replacement markets, the hope of US manufacturers and their congressional supporters is that the Joint Strike Fighter will become the next F-16 and secure the US industry with an unbeatable advantage in the future commodity fighter market. Greed is a powerful motivator in the Joint Strike Fighter program and one which is likely to see most of the obstacles to this aircraft, and its inherent limitations, ignored in the quest for market dominance. The history of the Joint Strike Fighter (formerly the Joint Advanced Strike Technology - JAST) program is by any measure colourful, its earliest origins tracing back to technology demonstration programs for a Harrier follow-on for the US Marine Corps and multirole fighter for the US Air Force (refer AA December 2001 and http://www.jsf.mil/). The shrinking US aerospace industrial base soon saw significant congressional pressure applied for the initial technology demonstration goal to be extended into a production fighter program. In its current shape the Joint Strike Fighter program could lead to the production of around 3,000 Joint Strike Fighter variants replacing US Air Force F-16Cs, A-10s, US Navy F/A-18Cs, and US Marine Corps and RAF/RN Harrier variants. The lead service in the Joint Strike Fighter program remains the US Air Force. From the very outset the principal aim of the Joint Strike Fighter program was to produce a low cost mass production strike aircraft which exploits the latest avionic/computer, stealth and production technologies. Given the incessant political threats of F-22 program cancellation held over the US Air Force through most of the 1990s, limiting the air superiority capabilities of the Joint Strike Fighter was a political imperative - moreso given that air superiority capabilities such as high thrust/weight ratio and sustained supersonic cruise are not very compatible with very low unit cost. If the Joint Strike Fighter were to be too snappy a performer in the air superiority game, the F-22 would have been promptly axed thereby shifting USD 20B or more of production costs back by at least a decade much to the delight of vote buyers in the US Congress. Indeed as recently as a year ago the US Air Force had to defend the F-22 against repeated political attacks, most of which clearly illustrated the almost total technical illiteracy of the F-22's critics. Invariably the argument is that the F-22 is too big, too costly, too capable or built around Cold War needs, thus irrelevant to the modern environment and that a Joint Strike Fighter can do the job well enough. The US Air Force crafted the basic definition of the Joint Strike Fighter - its size, performance, load carrying ability and target cost around its principal tactical strike fighter, the Lockheed-Martin F-16CG/CJ. In the mid 1990s US Air Force force structure model the F-15C flew air superiority and air defence tasks, the F-111F, F-15E and F-117A performed the deep strike penetration tasks, with the latter used in more heavily defended environments. The venerable Fairchild-Republic A-10A Thunderbolt was used for battlefield interdiction and close air support, together with the F-16CG. Defence suppression was performed by the F-16CG, in concert with AGM-130 firing F-15Es, after the retirement of the formidable F-4G Weasel. In this model targets fall into two distinct bands - those within a 400 NMI radius of friendly runways, and those at 600 NMI and beyond. This force structure model evolved during the latter part of the Cold War, and combined a relatively diverse mix of fighter capabilities. With the 1970s F-111F, A-10 and F-117A, 1980s F-15C/E and F-16C and a mix of weapons with lineages back to the 1960s, this model was a cumulative aggregation of almost three decades of technology and evolving doctrine. This was the force structure which the US Air Force applied with such devastating effect against the SovBloc modelled Iraqi defences in 1991 and it proved itself convincingly. There is however one important division which can be drawn through this force structure model - size. With the exception of the small single engine single seat F-16, all of these aircraft are large twin engine fighters designed to push the performance envelope in their respective categories. The ubiquitious F-16 was a uniquely Cold War phenomenon. With NATO and the Warsaw Pact geographically poised along either side of the Iron Curtain, presenting each other with a concentration of force and targets unprecedented in history, significant imperatives existed for both sides to saturate the theatre with high performance fighters. Whoever won the air superiority game over Central Europe held the decisive advantage in the Cold War standoff. Fighter combat radius and endurance over the target are not issues when the geographical environment puts the two largest military forces on the planet head-to-head across a single frontier. The Light Weight Fighter (LWF) contest saw the GD YF-16 take the laurels and decisive build numbers over the YF-17. The production F-16A was a day-VFR light weight air combat fighter designed for exceptional transonic agility and good supersonic dash performance when clean, armed with Sidewinders and an internal gun. Its principal role was to destroy enmasse the Soviet and allied Warpac strike fighter fleets in close air combat, and then swing into day-VFR battlefield air interdiction and close air support to eradicate Soviet/Warpac land forces, the latter role to be shared with the F-15A, F-4E and F-111D/E/F. With the Soviet/Warpac fighter fleets dominated by the MiG-21, MiG-23/27 and Su-7/17/22 series, the F-16s would have enjoyed a decisively target rich environment. With the impending retirement of the F-4E Phantom II, the US Air Force needed a substitute to fill the tactical fighter bomber role. The F-16C, equipped with the LANTIRN Terrain Following Radar and FLIR/laser targeting podset, was to fill this niche. With European theatre geography and threats driving this need, the radius of the F-16 airframe was yet again not an issue. When the Soviet Empire collapsed, the US Air Force was forced into a massive downsizing program. Under significant budgetary pressure, the remaining F-4E and F-4G aircraft were retired, followed by the F-15A, much of the F-16A fleet and early model F-111A/D/E/G aircraft. By the mid to late nineties, the US Air Force fighter fleet comprised primarily the F-15C, F-16C variants, the F-15E and a small number of F-117As. Most of the massive B-52 fleet was retired and the buy of B-2A batwing bombers was chopped from 132 to 60 and then finally 21. Expectations during this period were that the principal strategic problems the US would confront would be troublesome nations in the Balkans and the Middle East, with ethno-religious conflicts between smaller nation states dominating agenda. In this environment problem nations would be unable to threaten US basing, and the enormous political clout during the Pax Americana period would see easy access to basing. Concurrently the US Congress showed little interest in the defence budget, and the US Air Force faced the prospect of an aging and increasingly expensive to run fighter fleet, in a strategic environment where air superiority and safe in-theatre basing were virtually guaranteed. This was the environment which shaped the Joint Strike Fighter program - a situation in which combat radius, endurance over the target, air superiority performance and availability of in-theatre basing were not principal design imperatives. Cost and industrial base survival pressures were the foremost drivers in the Joint Strike Fighter program. The US Air Force needed a cheap mass production bomb truck to provide a one-for-one replacement of its aging F-16C inventory. The US aerospace industry needed another F-16A with which to saturate export markets and retain their eroding market position against the Dassault Rafale and Eurofighter Typhoon. Perhaps the greatest misconception about the Joint Strike Fighter program is that it represents a repeat scenario when compared to the YF-16/F-16A program - a low cost highly agile air superiority fighter designed to exploit cutting edge technology to provide a shorter ranging supplement to the top end twin engine large fighter (then F-15A, now F-22A) of the period. This misconception misrepresents the central design objectives of the Joint Strike Fighter program against the Light Weight Fighter program, and also ignores the decisive role in the F-16 fleet. In its day the F-16A was perhaps the nastiest close-in air combat fighter in existance, requiring careful tactics by even the top end F-15A air superiority fighter. While the F-16C Block 40/50 is heavier, it is still a respectable air combat fighter even if a dubious bomb truck. The F-16's central design optimisation was the transonic dogfight, reflected in thrust/weight ratio, wing loading, turn rates, climb rates and acceleration. In these parameters it was competitive against the best in the field, even if it could not compete with the thrust/weight ratio, wing loading, climb rates and acceleration of the F-15A. The Joint Strike Fighter's central design optimisation is in-theatre strike, battlefield interdiction and close air support, reflected in forward sector stealth, internal weapons/fuel capacity and cruise efficiency in clean configuration. In these parameters it outperforms the incumbent F-16C and F/A-18A/C, while providing relatively similar air superiority performance to these types. Against the current yardstick for air superiority performance, the F-22A, the Joint Strike Fighter is a non-contender - its 35 degree class transonic wing and 1:1 thrust/weight ratio are adequate for self-defensive purposes but not in the league for rapidly establishing air supremacy. Just as the joint Tactical Fighter eXperimental (TFX) or F-111A/B program was cast at an early stage into a conceptual mold of a high speed long range bomb-truck, the Joint Strike Fighter has been cast into the mold of an incrementally improved F-16C / F/A-18C class light bomb-truck, exploiting stealth and modern avionics to provide a survivability edge over its predecessors. The TFX program crashed and burned on the evolving needs of the US Navy, who wanted more air superiority performance and lower carrier landing weights. Some critics of the Joint Strike Fighter argue that it will inevitably go the route of the TFX experiencing cost growth, weight growth and performance loss as it undergoes development and its respective end users load it up with desired design extras to meet their specific needs. Indeed US reports suggest repeated political clashes in recent years, as the US Marine Corps and Navy sought performance and capability improvements which conflicted with US Air Force unit cost targets. Given that the maritime users of the Joint Strike Fighter do not have an F-22 equivalent to gain the high ground in an air battle, it is not inconceivable that we might see downstream disagreements in the Joint Strike Fighter program as these players try to fill this crucial gap in their basic capabilities. The broader strategic issue for the Joint Strike Fighter will be its basic sizing in a world environment which sees two mutually supporting strategic trends - problem nations acquiring ballistic missiles, both mobile and semi-mobile, weapons of mass destruction, and a concurrent trend to implementing shoot-and-scoot SAM/AAA air defence tactics. In air power theoretic terms, the use of shoot-and-scoot SAM/AAA and ballistic missile/WMD technologies represent an anti-access strategy. Such strategies aim to deny the use of nearby runways by threatening ballistic missile or WMD attacks on runways as well as hosting nations, while providing a persistent and highly mobile air defence threat (A good summary of emerging ballistic missile capabilities in this area is at the FAS website : Iran, North Korea). Prior to the 11th September, long term US Air Force envisaged a two tier force structure model: the Global Strike Task Force (GSTF) , an Air Expeditionary Force comprising 48 x F-22A and 12 x B-2A, would break the opponent's air defences and launch high tempo attacks on critical command/control/communications, WMD sites and ballistic missile forces. As the opponent's defences would crumble, a sustainment Air Expeditionary Force, comprising the Joint Strike Fighter, B-1B and B-52H, would then hammer the opponent to collapse. This model makes two implicit assumptions - the enemy cannot bombard friendly runways with ballistic missiles, and these runways are close enough to permit a viable sortie rate (missions/day) by the Joint Strike Fighter and F-22. If the opponent chooses to play the ballistic missile bombardment game, then this model does get into some difficulty, since the 400-600 nautical mile range of evolved Scud class missiles presents difficulties for the Joint Strike Fighter - nearby nations might deny basing access and bases which are made available might be shut down by ballistic missile strikes. This is less of an issue for the supercruising F-22, as with decent tanker support it can sustain a high sortie rate from a much greater distance - the F-22 can transit to targets at roughly twice the speed of contemporary fighters and the Joint Strike Fighter. This was a principal strategic argument against the whole concept of the Joint Strike Fighter prior to the September 11th events. Since then we have seen a pivotal in bombardment tactics, with long endurance loitering bombardment used to successfully engage and destroy fleeting and highly mobile ground targets. This in turn mitigates against smaller fighters and decisively favours aircraft which have larger bomb loads and endurance. The argument that Afghanistan was a one-off does not hold up to scrutiny - a campaign against Iran, Iraq, the PRC or more than one African problem nation could see the very same geographical problem issues arise yet again. Well spoken diplomacy is no match against the threat of domestic terrorism across porous Third World borders, or ballistic missile attacks with conventional or even WMD warheads - all being convincing disincentives to the basing of a US-led Air Expeditionary Force. Whether one is hunting a high technology Russian mobile SAM system, a mobile ballistic missile system, or a bunch of terrorists in a four wheel drive or BTR-60, the inevitable reality is that the best technique is loitering bombardment which is not the forte of smaller fighters - including the Joint Strike Fighter. The

revived argument in the US promoting new build B-2C batwings and

an F-111/FB-111A class regional bomber illustrates this important

in the bombardment paradigm - and the increasing long term

exposure of close-in based Air Expeditionary Forces to MRBM attacks.

The

argument pits direct operational needs for striking radius, sortie

rates

and bombloads in difficult to export or non-exportable top tier assets

against the limited yet highly exportable and thus potentially

profitable JSF.

Part 2 will compare the F-35/JSF against some in service and production fighter types.

|

|

|

| The USAF intend to use the F-35/JSF as a one-for-one replacement aircraft for their aging fleets of F-16C strike fighters and A-10A battlefield interdictors. Against both types the F-35/JSF provides a significant survivability improvement by virtue of its stealth capability, while it outranges the F-16C on typical strike profiles. The air superiority and air defence tasks of the F-15C and deep penetration tasks of the F-15E and F-117A will be absorbed by the supercruising stealthy F-22A Raptor (US Air Force photos). |

|

| The USN aim to use the F-35/JSF as a replacement for the older F/A-18A-D models, to provide a survivable first day of the war strike fighter to supplement the reduced observable F/A-18E/F in carrier air wings. The navalised JSF has larger wings, stabilators and marginally more fuel than the USAF variant. It will provide a respectable combat radius gain over the F/A-18A-D but will not match the performance of the long departed A-6E Intruder (USN). |

|

|

The USMC, RN and RAF will

use the

STOVL F-35/JSF variant to replace a range of Harrier variants for

operation from unprepared FOBs and STOVL carriers. With a supersonic

dash capability, significantly better radius performance and a modern

radar, the F-35/JSF is a vast improvement over the sixties technology

Harrier family. The Shaft Driven Lift Fan technology will provide

better

hover performance than the Harrier (US Marine Corps). |

|

|

Current USAF planning sees the establishment of the Global Strike Task Force (GSTF) comprising 48 F-22As and 12 B-2As. This silver bullet expeditionary force is intended to demolish opposing air defences and critical WMD targets in the opening phase of an air campaign, upon which a sustainment force of legacy B-52H/B-1B and F-35/JSF fighters completes the bombardment. The JSF is predicated upon having runways within a 400-600 nautical mile class distance of intended targets, thus aligning the aircraft firmly with Cold War period geographical assumptions - a precondition which may not be met in future conflicts (US Air Force). |

|

| A key issue for the JSF will be the proliferation of medium range ballistic missiles in the 600+ nautical mile range class. With North Korea having supplied this technology to Iran and Pakistan the long term outlook is that proliferation will be very difficult if not impossible to contain. While a supercruising F-22 can sustain a high sortie rate over such distances, the subsonic cruise optimised JSF will suffer a debilitating reduction in sortie rates as distances push out well beyond the design point of 600 nautical miles - both types requiring generous aerial refuelling support (Author/LM). |

|

Part 2 Sizing up the Joint Strike Fighter

The public rhetoric surrounding the Joint Strike Fighter is no less deceptive to the uninitiated as the public rhetoric surrounding many of the other current production types being bid for AIR 6000. In all instances we hear the latest avionics technology and stealth performance as key attributes of a modern high tech fighter designed to meet the threats of the future. In comparing the Joint Strike Fighter against the Eurofighter Typhoon, Dassault Rafale, F-16C/B60 and F/A-18E/F, the Joint Strike Fighter will have a decisive advantage in its very moden integrated avionic architecture, which is modelled on that of the F-22A but built using militarised commercial computing technology. With a battery of GigaHertz clock speed processors, high speed digital busses with around 1,000 times the throughput of the Mil-Std-1553B busses in the teen series and Eurocanard fighters, it is no contest - the Joint Strike Fighter is in an unbeatable position. While growth versions of the teen series and Eurocanard fighters might see a similar integrated avionic architecture in the post 2010 period, this is unlikely to be a revenue-neutral design change. Against all of these contenders, the Joint Strike Fighter has an unassailable survivability advantage in its use of evolved second generation stealth technology, again derived from the F-22A technology base. With a forward sector radar cross section cited to be close to the F-22 the Joint Strike Fighter will present a challenging target to forward sector radar guided threats. As a bomb truck, the Joint Strike Fighter falls into a similar payload class to these players, but with the important distinction that it carries its bombs or missiles internally, and it has an internal fuel capacity similar to that of these competing aircraft loaded up with external fuel tanks. In practical terms this means that the Joint Strike Fighter can carry a similar load of fuel and bombs without the critical transonic regime drag penalty of external stores. Therefore it can carry the same bomb load further using a similar fuel load. Claims that the X-35 demonstrator exceeded the Joint Strike Fighter combat radius requirement should come as no surprise - the cited figure of 600+ nautical miles is credible and a distinct gain over the F-16C and F/A-18A/C. This radius is however unlikely to be acheivable if the F-35 is heavily loaded with external stores, since it will like its competitors incur a major drag penalty. Claims that the Joint Strike Fighter is an F-111 class bomb truck are scarcely credible, especially if the F-111 is armed with internal JDAMs or small bombs - a variable geometry wing and 34,000 lb of internal fuel is impossible to beat in the bomb trucking game. The comparison of a clean F-35 against an F-111 loaded with external BRU-3A/Mk.82 is not representative of what a post 2020 F-111 weapons configuration would look like. The only decisive system level advantage the Joint Strike Fighter has against the F-111 is its use of second generation stealth technology - no radar cross section reduction on the F-111 will make it competitive against this type. In terms of avionics, if the RAAF retains the F-111 post-2020 then Joint Strike Fighter generation technology would most likely find its way into the Pig and thus render this comparison meaningless. As an air combat fighter the Joint Strike Fighter is more difficult to compare, since the differences against the teen series and Eurocanards are less distinct. In terms of achievable radar performance its small aperture radar will fall broadly into the same class as its direct competitors. While transonic turn rate performance figures remain classified, the F-35 is a 9G rated fighter and is thus apt to deliver highly competitive transonic close-in dogfight performance against the teen series and Eurocanards. The empty weight of the F-35, at 26,500 - 30,000 lb is deceptive insofar as it must be compared against a conventional competitor's weight including external pylons and empty fuel tanks - nevertheless it is in the empty weight class of an F-15 or F/A-18E rather than F-16C or F/A-18C. With a nominal payload of 2,000 lb of AAMs the USAF F-35 yields a combat thrust/weight ratio around 1.1:1 which is competitive against a modestly loaded F-16, F/A-18A/C or Eurocanard, but with a typically better combat radius or combat gas allowance - however it is not in the class of an F-15C let alone F-22A. Therefore the F-35 should provide competitive acceleration and climb performance at similar weights to the F-16, F/A-18A/C or Eurocanards. With the upper portions of the split inlets likely to produce good vortices, the F-35 should provide respectable high alpha performance and handling, especially if flight control software technology from the F-22A was exploited fully. Where the F-35 is apt to be less than a stellar performer is in the supersonic Beyond Visual Range combat regime, which is the sharp end of air superiority performance. This is primarily a consequence of the wing planform design which is in the 35 degree leading edge sweep angle class, thus placing it between the sweep of the F/A-18A/C and F-16A/C. Wing sweep in this class is good for transonic bomb trucking and tight turning, but incurs a much faster supersonic drag rise with Mach number against the supersonic intercept optimised wing planforms seen in the F-15, Typhoon, Rafale and indeed the F-22A. The important caveat is that the teen series and Eurocanards wear a hefty supersonic drag penalty from carrying external missiles and drop tanks, whereas the F-35 will have a clean wing in this regime. In the absence of published hard numbers for supersonic acceleration, energy bleed and persistence performance, the only reasonable conclusion is that the F-35 is likely to be competitive against the teen series and Eurocanards in combat configuration but decisively inferior to the F-22A. Another factor in the BVR game is radar performance, limited by the power/aperture of the radar design. While hard numbers on the F-35's radar are yet to be published, what is available suggests an 800-900 element phased array which is in the class of the F-16C/B60, F/A-18E/F and Eurocanards but well behind the massive 2200 element APG-77 in the F-22A. With a superior processing architecture to the F-16C/B60, F/A-18E/F and Eurocanards the Joint Strike Fighter is very unlikely to have inferior radar performance, but may not have a decisively large detection range advantage either. If used as an air defence interceptor and air superiority fighter, the F-35 will deliver similar capabilities to the F-16C/B60, F/A-18E/F and Eurocanards at similar weights - its limitations in thrust/weight ratio and thus climb rate/acceleration, and wing optimisation for transonic regimes, will limit its ability to engage high performance supersonic threats by virtue of basic aerodynamic performance. Its small radar will also put limitations on achievable BVR missile engagement ranges, although this will be mitigated by very good forward sector stealth performance. A threat with a large infrared search and track set may however get a firing opportunity in a high altitude clear sky engagement. The radar performance bounds will also present similar limitations to those seen with the F-16C/B60, F/A-18E/F and Eurocanard series when hunting for low flying cruise missiles - without close AWACS support the F-35 may not be very effective in this demanding role. It is worth noting that the F-35 is not an all-aspect stealth design like the F-22A and YF-23 which have carefully optimised exhaust geometries and thus excellent aft sector radar cross section. The axisymmetric F-135 nozzle is not in this class and thus the F-35 is clearly not intended for the deep penetration strike role of the F-22A. Attempting to make an all encompassing comparison of the F-35 against current fighters is fraught with some risks, insofar as the design will further evolve before production starts and many design parameters, especially in avionics, may . In terms of basic sizing and performance optimisations probably the best yardstick is that the F-35 is much like a stealthy but incrementally improved F/A-18A/C which closely reflects the similarity in the basic roles of the two types - strike optimised growth derivatives of lightweight fighters. The F-35 is clearly out of its league against the F-22A in all cardinal performance parameters, with the exception of its bomb bay size which is built to handle larger weapons than the F-22A. Disregarding stealth capability and baseline avionics, the F-35 is also out of its league against the F-111 in the bomb trucking role by virtue of size and fixed wing geometry. All of these analytical arguments are essentially contingent upon the JSF meeting its design performance and cost targets. This remains to be seen since the JSF is arguably the highest technological risk program in the pipeline at this time. Key risk factors derive from its reliance upon bleeding edge technology to achieve the combination of capability for its size and cost. There are no less than five areas of concern: the COTS derived avionic system departs from established technology and is in many respects a repeat of the F-111D Mk.II avionics idea; the reliance upon software goes well beyond established designs and software systems with many millions of lines of code are not reknowned for timely deliveries; any durability problems with the hot running F135 engines would be handled by derating which cuts into an already marginal thrust/weight ratio; differing needs and expectations by the JSF's diverse customer base could cause divergence in program objectives and cost blowouts in common areas; the sheer complexity of what the JSF project is trying to achieve in melding untried technologies with diverse missions could create unforseen problems in its own right. Until we see production JSFs coming off the production line, it remains a high risk option. The Joint Strike Fighter is a most curious blend of the F-22 technology base, state-of-the-art avionics and Cold War era strategic thinking - in its own way as much a Cold War anachronism as the Eurocanards. Insofar as one of its prime design aims is to shoot down the Eurocanards in the commercial dogfight, it represents an instance of an anachronistic fighter sizing strategy and associated cost structure becoming a principal design driver over achievable combat effect and long term strategic usefulness. Joint Strike Fighter vs A6K With the F-35 being the holy grail of budget minded force planners throughout the West, it has developed some followers in the Canberra defence establishment, especially amongst players who see little importance in the RAAF's established doctrinal and strategic thinking or developing regional environment. Indeed, if we pretend that the PRC doesn't exist and India's strategic competition with the PRC in the region doesn't concern us, and that cruise missiles are not the hottest selling item across the wider region, then the F-35 becomes an attractive proposition - a cheap to buy, cheap to run, stealthy hi-tech fighter which is an incremental improvement over the RAAF's somewhat anaemic F/A-18A Hornet. As a bomb truck, disregarding stealth performance, the F-35 falls into the gap between the F/A-18A and F-111. As an air combat fighter, it will offer modest performance gains over the F/A-18A HUG and the advantage of stealth. In the eyes of many this is apt to be a good compromise at a good price. These arguments may appear superficially reasonable, but are based upon a number of premises which are not reasonable. Regional strategic issues may have disappeared from the press and TV bulletins but remain as they were a year ago:

The sad reality is that the regional strategic drivers remain as is - they are a consequence of the ongoing economic and military growth in Asia. While India's current relationship with the West has thawed, this situation may not persist over coming decades - the strategic timeline which concerns A6K planning. What the War on Terrorism will produce, other than major strategic changes in the Middle East and Central Asia, is an increased move to mobility in Asian armed forces as the Afghan campaign is understood fully. It is also apt to produce a longer term demand for coalition campaign forces to support the US in expeditionary warfare. If we make the assumption that A6K will aim to field only new technology fighters with a very long term development future, then the only relevant candidates are the F-22 and F-35 - both stealthy and using the latest generation avionic architectures and engines. Numerous strategies exist - with or without F-111 replacement - for implementing the A6K program. If the F-111 is to disappear in 2015-2020, then the choices are a single type replacement using only the F-22, or only the F-35, or some Hi-Lo mix of the F-22 and F-35. If the F-111 is to be stretched beyond 2020, then the F/A-18A could be replaced with either the F-22 or the F-35. This provides no less than 5 possible force structure models, each with different funding needs and capability mixes. Which is best? That depends on the priorities of the observer. The case for a mix of F119 powered F-111s and F-22s was argued in some detail in AA late last year and presents a robust case in capabilities, with the benefit of significant domestic spending but the drawback of some developmental risk. The case for an F-22 and F-35 mix depends crucially on the perceived importance of bomb-trucking performance vs survivability of the F-35 against the F-111. The F-35's stealth advantage must be weighed against the F-111's superior ability to haul big loads over big distances - with an F-22 escort to kill opposing fighters and SAMs the survivability argument may prove narrower than many may think. A mix in which transonic F-35s escort supercruising F-111s is arguably non-viable and is merely a new technology reimplementation of the existing F/A-18 and F-111 mix. The alternatives of single type total force replacements with the F-22 or F-35 also raise interesting issues. While the F-35 at this time carries larger bombs than the F-22, it is a decidely inferior performer in the air combat game and the deep penetration strike game. With supercruise capability in a baseline bombing role using small bomb payloads the supercruising F-22's higher sortie rate at longer ranges suggests that one F-22 can perform a similar workload to a pair of F-35s, with the caveat that two or more F-35s will be needed to perform the air defence coverage of a single F-22. In terms of deterrent credibility and potency in combat, the F-22 is unbeatable, in terms of political whining from air power detractors of every ilk, it is a guaranteed magnet (deja vu - F-111 1967?). Conversely, a pure F-35 force structure is apt to leave important capability gaps in air superiority, cruise missile defence and deep penetration strike, while pushing up total numbers and thus aircrew demands - the latter likely to be a major long term issue with ongoing demographic shifts. A key factor in any F-22 vs F-35 contest is that the F-35 order book is full, but the F-22 buy was hatcheted from around 750 down to 332 thus providing significant incentives for an export sale of an aircraft which would be exclusively available, like the F-111 during the 1960s, only to close and trusted allies of the US. US sources suggest a revived build of 750 F-22s would push the unit cost down to USD 74M, similar to an F-15E. Which of these strategies proves to be most attractive to Australia's leadership is yet to be seen - and if the government is serious about the A6K effort this will not be known until a decision is reached around the middle of the decade. What is clear at this stage is that the fighter market is stratifying in a manner without precedent - two decades ago a buyer had more than one choice in any given size/weight/performance class. By 2010 this will be untrue - in non-stealthy fighters there is apt to be only the F/A-18E/F and Typhoon with different weights, aerodynamics and mission avionic capabilities, and in stealthy fighters the F-22 and F-35 which are much more diverse in capabilities than their teen series predecessors, the F-15 and F-16. Therefore a choice of fighter will determine the choice of strategy/doctrine since different classes of fighter provide distinctly different possibilities - and limitations - in roles and missions. One might ask the question of whether the classical model of a fighter competition is even relevant any more? With the only gains from the competitive process likely to be in ancillary benefits such as domestic support programs - aircraft prices being largely fixed by the domestic markets of the manufacturers - one might seriously contemplate the primary focus of the A6K evaluation being in assessing the ability of particular fighter types or mixes/numbers thereof to perform the intended roles, rather than the historical game of playing manufacturers off to secure the best pricing package. In the context of A6K, the

F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is most notable in terms of the roles and

missions it cannot do well, rather than those it can. If air

superiority

and long range strike are the long term priorities which government

policy ostensibly declares them to be, then the F-35 may not be the

best

choice for replacing the F/A-18A or the F-111, either singly or in a

mix.

|

|

|

The comparison table is

based

upon

provisional data and some assumptions about profiles and weapon loads.

Nevertheless, it illustrates the significant disparity between the

F-111, F/A-18A and F-35/JSF in the critical loitering bombardment

regime

against mobile targets. Loiter performance is also relevant for air

defence operations as it determines how frequently the fighter must top

up from a tanker to maintain station at a given radius [Ed: NB the

F/A-22A fuel figures represent pre-FSD/LRIP configuration] (Author,

L-M). |

|

|

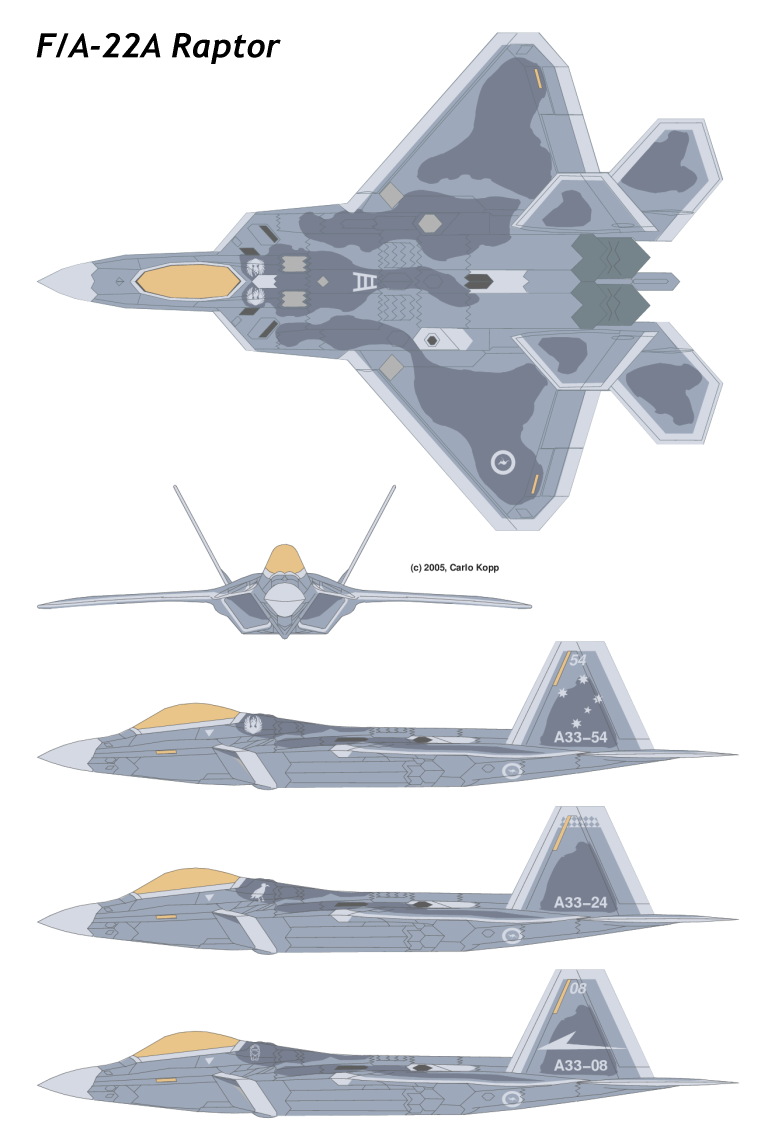

The F-35/JSF is frequently

portrayed as a cheaper, single engined F-22. This is a dangerous

misrepresentation, since key design optimisations in the JSF wing and

thrust/weight ratio make it anything but a performer in the class of

the

F-22A. The F-22A offers all aspect low observable (stealth) performance

intended for deep penetration strikes, and is much superior to the

F-35/JSF. With the ability to penetrate higher, faster and with greater

stealth, the F-22 is a significantly more survivable strike aircraft

than the F-35/JSF (USAF). |

|

|

Probably the best

contemporary

equivalent to the F-35/JSF is the late build F/A-18C which is primarily

used as bomber in USN service. The F-35/JSF is an incremental

improvement over the F/A-18A-D in virtually every parameter, and has

low

observable performance which no teen-series or Eurocanard can compete

with. The F-15C class empty weight and 18-19 klb class internal fuel

capacity of the F-35/JSF are deceptive - as a stealthy aircraft it must

carry internally the fuel an F/A-18A-C carries in external tanks on a

basic profile (RAAF). |

|

|

The F-35/JSF is often

described

as

a natural F-111 replacement due to its basic design optimisation for

bomb trucking. This comparison is highly misleading, insofar as the

USAF

regard the F-111A/C/D/E/F/FB-111A as being in the regional bomber

category rather than strike fighter category. With just over 50% of

the internal fuel capacity of an F-111, the F-35/JSF cannot be directly

compared. In strike operations the F-35/JSF has one genuine advantage

over the F-111 - third generation low observable technology - which

makes it much more survivable against top end SAM threats (RAAF). |

|

|

The F-35/JSF is likely to devastate the Eurocanards in the export market, as most potential clients in the Far East, Middle East and Europe will be attracted to the F-22 generation avionic package, stealth capability and performance gains over their existing F-16A-D and F/A-18A-D export fighters. In an environment where top end air superiority performance and combat radius are non critical performance parameters, the F-35/JSF is apt to be an attractive proposition. The Australian environment, where combat radius and air superiority performance are vital for a small force defending a large area, is not the design target of the JSF (USAF). |

|

|

|||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

|||||||||||||

| Artwork, graphic design, layout and text © 2004 - 2014 Carlo Kopp; Text © 2004 - 2014 Peter Goon; All rights reserved. Recommended browsers. Contact webmaster. Site navigation hints. Current hot topics. | |||||||||||||

|

Site Update

Status:

$Revision: 1.753 $

Site History: Notices

and

Updates / NLA Pandora Archive

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Tweet | Follow @APA_Updates | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||