|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433] Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433]](APA/APA-Title-Analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433] Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433]](APA/APA-Title-Analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assessing Joint Strike Fighter Air Combat Capabilities |

|||

|

|||

Given that the simulations cited by the Joint Strike Fighter program office and manufacturer disagree so dramatically against what is known about the capabilities of recent Flanker variants, and their supporting systems, there is a strong case to be made for all of these simulations to be fully audited by an independent body such as RAND or CSBA to determine whether representative adversary capabilities, tactics, doctrine and supporting systems were actually employed. Such disparities between assessments and fact parallel the findings of GAO in vendor and program office cost assessments in the Joint Strike Fighter program, reinforcing the case for a comprehensive Independent Verification and Validation effort on the program's activities. Depicted SDD Joint Strike Fighter Prototype AA-1 in flight. This aircraft is a 'non-representative prototype' which predates a series of structural and systems weight reduction measures. (Imagery via Air Force Link).  |

|||

|

|||

| The

ongoing debate surrounding the Joint Strike Fighter has seen some

remarkable claims made recently by the F-35 program executive

officer, Maj. Gen. Charles R. Davis, and the Lockheed Martin

executive vice president of F-35 program integration, Tom Burbage.

The central argument in these claims by the program executives is

that the Joint Strike Fighter will outperform Russian designed

“Sukhois” in air combat operations, indeed the opening

statement in the manufacturer's media release claims “F-35

Lightning II is at least 400 percent more effective in air-to-air

combat capability than the best fighters currently available in the

international market.” However, remarkable claims require remarkable evidence, and to date no such evidence has been forthcoming either from the program office or the manufacturer. Historically, when Joint Strike Fighter advocates have been challenged to provide the supporting assumptions and methodology that were used to compare Joint Strike Fighter capabilities to potential adversary aircraft, the answer has invariably been “this is classified so we cannot tell you”. That in itself is a dubious claim, insofar as such analyses generally involve classification of exact results, but not necessarily classification of how the assessment was performed and which adversary capabilities were assessed. The most interesting of the recent claims are that the “F-35 enjoys a significant Combat Loss Exchange Ratio advantage over the current and future air-to-air threats, to include Sukhois,” made by Maj. Gen. Charles R. Davis, F-35 program executive officer, and that “the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II is at least 400 percent more effective in air-to-air combat capability than the best fighters currently available in the international market” made by the manufacturer’s public relations office. Both claims were justified by reference to “U.S. Air Force air-to-air combat effectiveness analysis” and “Air Force's standard air-to-air engagement analysis model, also used by allied air forces to assess air-combat performance, pitted the 5th generation F-35 against all advanced 4th generation fighters in a variety of simulated scenarios.” Importantly, these claims did not specify whether the results were for Within Visual Range (WVR) or Beyond Visual Range (BVR) air combat, or some mix of the two. Which variants of the Sukhoi Flanker, or other types assessed, were also not disclosed. The reader was left to infer that the simulations covered a mix of engagement types, and all aircraft types which the Joint Strike Fighter might confront in combat. If we consider real world air combat scenarios, there are a wide range of variables which can be applied to constructing a scenario. Some basic considerations include:

These considerations, which represent assumptions about Joint Strike Fighter weapon types and payloads, and assumptions about adversary aircraft types, tactics, employment, radar design, missile design, and supporting radar and sensor system design, will all have a large impact on the results of any simulation. Therefore, the “exchange ratio”, or how many “hostiles” are killed versus “friendlies” lost, can vary significantly depending upon how these variables are set up. In any aerial clash between two fighter forces, contemporary thinking is to engage and destroy as many opposing fighters as possible at Beyond Visual Range, such that an advantage in numbers can be gained when the surviving enemy fighters close to visual range. At that point, the objective is to gain firing opportunities at visual range before the opponent does, again to inflict losses on the enemy as quickly as possible. The long history of aerial combat shows that the highest numbers of kills were accrued by pilots who practiced surprise ambush tactics against unsuspecting opponents, and avoided close combat manoeuvring engagements. The very same history shows that pilots flying escort or air defence patrols scored, on average, much fewer kills. Many historical case studies have revealed frequent and ongoing arguments between fighter pilots seeking to fly independently to maximise opportunities for kills, and those whom they were tasked with protecting, who sought to tether the fighters to their vulnerable assets – be they bombers or surface targets. This dichotomy is one of the unwanted realities of aerial war – wiping out the opponent's air force favours independent fighter operations, and ambush tactics, yet keeping critical surface and airborne assets alive requires that fighters orbit close to these assets to defend them from attacks. Once fighters are committed to protecting an airborne or surface based asset, they will have no choice other than to patrol a volume of airspace between those assets and the approaching enemy force. The unavoidable geometrical reality is that the area in which they are operating will be therefore well known to the enemy, the instant the location of the asset is known to the enemy. What follows in turn is a set piece engagement scenario, where the defender plays to keep the attacker away from the defended assets, and the attacker plays to overwhelm or bypass the defenders. In the contemporary air combat game this set piece scenario unfolds in three phases:

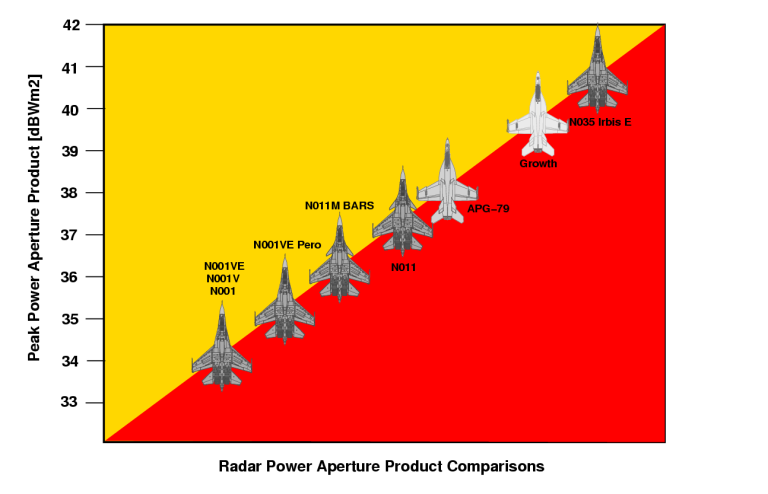

These realities are also key factors which have determined the design foci in the Russian Sukhoi Flanker family of fighters, especially the most recent variants. The Flankers are designed to deliver large salvoes of Beyond Visual Range missiles to kill as many defending fighters as early as possible, and force evasive manoeuvring upon the survivors to “spoil” their entry geometry once the Flankers close to visual range and merge. The Flankers are built to excel in close combat, exploiting the refined aerodynamic design of the aircraft, thrust vectoring capability, and high thrust to combat weight ratio. The notion that air combat will be wholly confined to Beyond Visual Range combat presupposes that an adversary will agree to play this game, even if it is not to their advantage. Real adversaries do not play in this fashion, and never have. The claim that the Joint Strike Fighter is “at least 400 percent more effective in air-to-air combat capability” therefore needs to be carefully tested against the realities of modern air combat. The notion that an aircraft with unspectacular aerodynamic performance, very limited missile payload, and strongly compromised stealth, is at least half as good as the top tier F-22 is remarkable by any measure. More so since the Joint Strike Fighter lacks the supersonic cruise capability, radar peak power, subsonic and supersonic agility, and all aspect penetration orientated stealth capabilities of the larger F-22. If we assume that the cited 400 percent is an “exchange ratio” as the statement expects us to infer, it could apply to Beyond Visual Range combat or a mix of Within Visual Range and Beyond Visual Range. However, the claim cannot apply to Within Visual Range combat alone since all Flankers have better manoeuvring capability in close combat, and like the Joint Strike Fighter are equipped with Helmet Mounted Display/Sight technology. Even if we assume they are both equipped with identical missile types, the Flanker's superior agility and performance, and larger payload of missiles, would result in a decisive advantage over the Joint Strike Fighter. The RAND presentation's observation that the Joint Strike Fighter is “double inferior” to the Flanker in close combat is an unavoidable reality of the Joint Strike Fighter's inferior speed, acceleration, combat thrust to weight ratio, and much higher effective wing (ie lifting area) loading. At present time the only air to air missile payload planned for the Joint Strike Fighter before 2018 is a pair of internally carried AIM-120 AMRAAM Beyond Visual Range missiles. British Joint Strike Fighter's are to have the option of carrying the ASRAAM Within Visual Range missile instead. In close combat the best the Joint Strike Fighter can achieve against any Flanker is parity, or a 1:1 exchange ratio – trading one Joint Strike Fighter for every Flanker killed. This is as generous an assessment as is possible, given what we know about the Joint Strike Fighter's aerodynamic performance inferiority relative to the Flanker. If the cited 400 percent applies to a 50:50 mix of Within Visual Range and Beyond Visual Range engagements, then it follows that to achieve a 4:1 ratio, the Joint Strike Fighter must achieve a 7:1 exchange ratio in Beyond Visual Range engagements. That is effectively claiming that it can almost match the F-22 regardless of the fact that it lacks all of the F-22's additional performance, sensor and stealth capabilities, and it carries at best one half the missile payload of the F-22, and at worst one quarter. That a Joint Strike Fighter which is optimised for subsonic combat at medium to low altitudes can almost match the F-22 in air combat exchange ratios against advanced Flankers like the Su-35BM or Su-35-1 presents a clear non-sequitur. The only way a simulation can produce this type of result is if the adversary aircraft are operated in a completely asymmetric environment, with pilots and operational planners who actively cooperate in getting themselves killed by:

The only feasible explanation for such results is therefore that the simulated engagements were flown by Joint Strike Fighters against legacy Flanker variants with low power N-001 radars, 1980s generation missiles, warning systems, defensive jammers, and supporting systems. In other words, a 2015 Joint Strike Fighter with its supporting systems is pitted against a 1980s threat without its supporting systems. Such results are only useful in assessing the effectiveness of the Joint Strike Fighter against some African or Middle Eastern nations and are clearly not representative of the Asia-Pacific environment post 2010. |

|||

Su-35BM cockpit layout. At this

time there

are three discrete generations of the Flanker. The first generation was

deployed during the 1980s and is represented by the baseline Su-27S/SK

Flanker B, Su-27UB/UBK Flanker C. Direct derivatives of the first

generation Flanker include the smart weapons capable Su-27SMK,

Su-30MKK/MK2 and Chinese clone J-11B. Second generation Flankers are

the Su-30MKI and Su-30MKM and the Su-27K/UB/Su-33/33UB which

incorporate additional capabilities such as thrust vectoring and phased

array radars. The third generation of Flankers is exemplified by the

Su-35BM and new production Su-35-1 which expand on second generation

features, but include high power-aperture phased array radars, advanced

Infrared Search Track systems, advanced networking, 200 nautical mile

class "counter-ISR" missiles, and are fully digital (Sukhoi).

The

MiG-35

Zhuk AE AESA multimode radar designed by Phazotron is

the first Russian

AESA design. An enlarged variant is in development, intended to deliver

similar power aperture performance to the F-22's APG-77 and F-15C's

APG-63(V)3/4, strongly outperforming the APG-81 in the Joint Strike

Fighter (RSK MiG).

|

|||

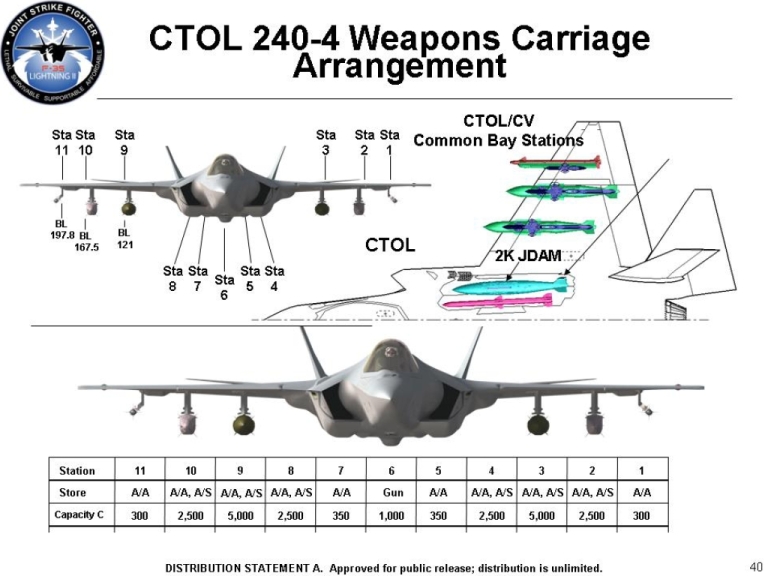

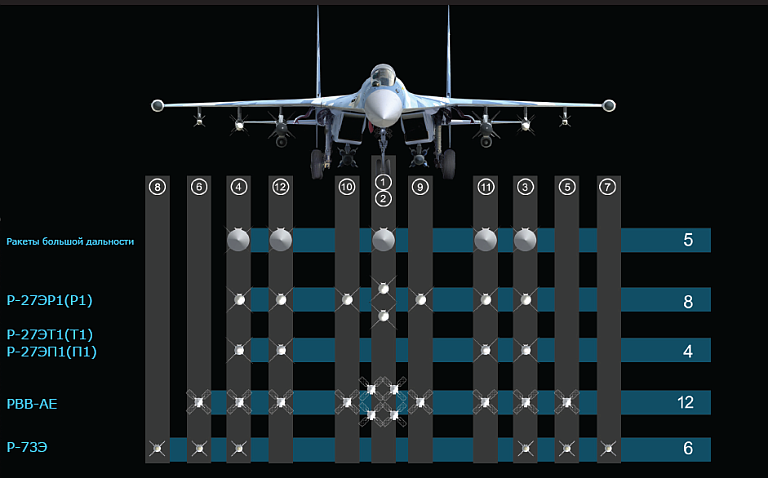

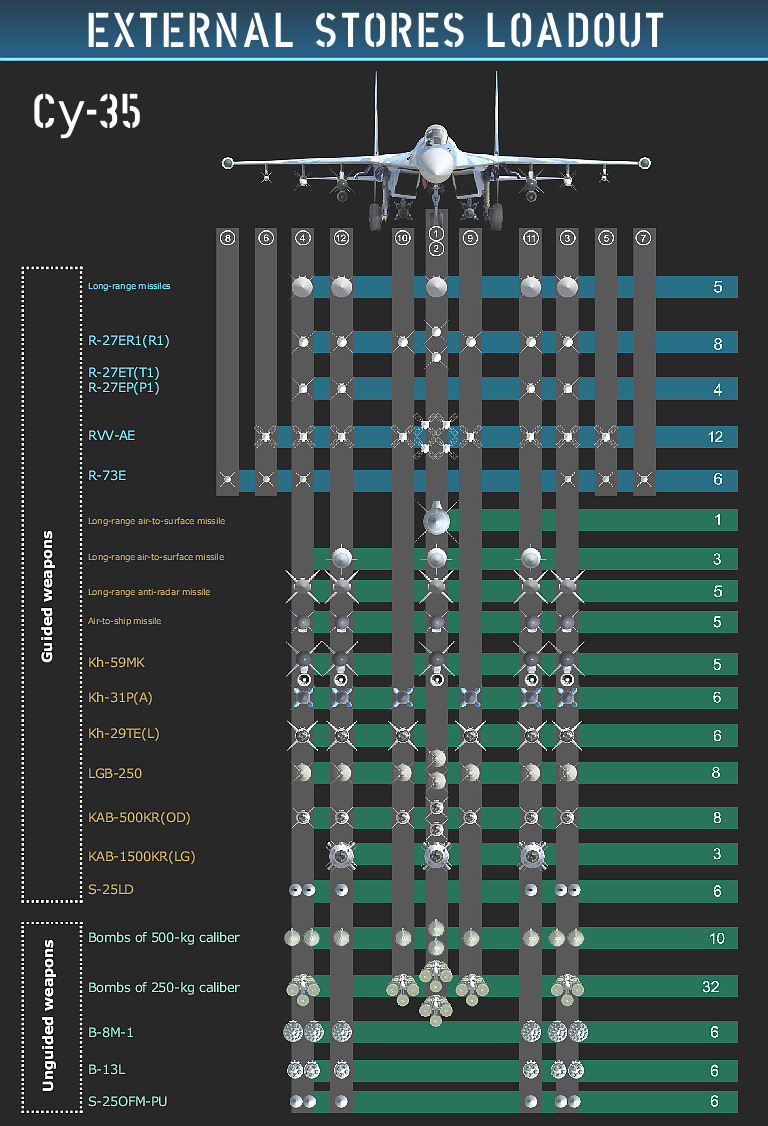

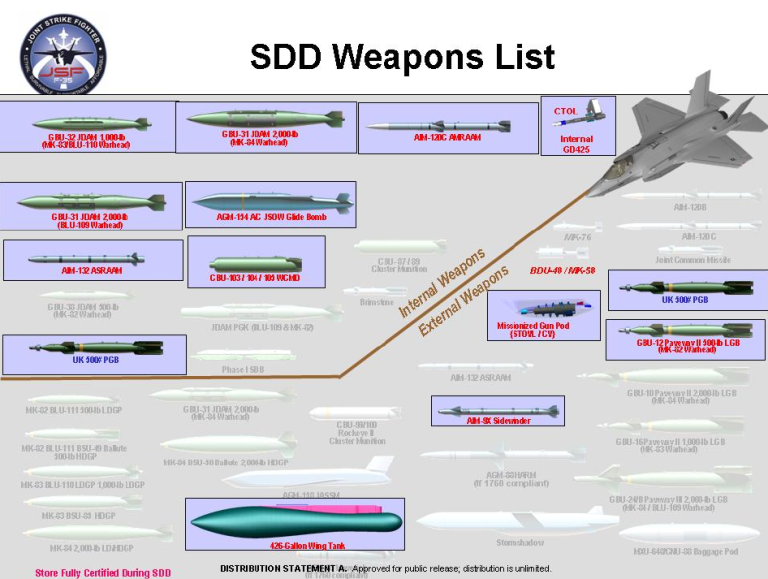

In the simplest of terms, the Joint Strike

Fighter is "outgunned" when confronting the Flanker in air combat. With

two to possibly four missiles carried, the Joint Strike Fighter

confronts an adversary armed with up to 12 missiles (above, from

www.jsf.mil, below KnAAPO).

2005

SDD Threshold Weapons. Early F-35s will carry only two internal

missiles, either the AIM-120 AMRAAM or ASRAAM. While growth to four

missiles remains planned, timelines have not been disclosed to date

(www.jsf.mil).

|

|||

The Joint Strike Fighter cannot achieve a high exchange ratio against an aircraft like the Su-35BM or Su-35-1 for a number of very good reasons:

The reality is that the “threat environment” the Joint Strike Fighter will confront in the Asia-Pacific is very different to the environment expected and envisaged when the Joint Strike Fighter was conceived during the early 1990s. There have been significant technological advances in two metre band radar, passive emitter locating systems, infrared sensors and high power-aperture X-band phased array radars. Moreover, DRFM jammers are proliferating, and Flankers now have the option of towed decoys like the KEDR.  Depicted an Su-35 Flanker E (KnAAPO Image) Central to the Joint Strike Fighter's weaknesses in air combat is its limited payload of internally carried missiles, which simply compounds the problems arising from the Joint Strike Fighter's inferior aerodynamic performance relative to advanced Russian designed fighters. The baseline for the Joint Strike Fighter is a payload of only two AIM-120 missiles, with long term growth to four internal missiles feasible. The claim that six 'superpacked' missiles might be carried remains to be demonstrated.  QF-4 drone. In combat the AIM-120 AMRAAM has delivered kill probabilities of the order of ~50 percent against targets which cannot be considered challenging either aerodynamically or electronically. The standard drone against which the AIM-120 has been tested, including the latest AIM-120D prototypes, is the QF-4, which is not capable of replicating the performance of any Flanker variant, especially not second generation Flankers with thrust vectoring, and third generation Flankers with supersonic cruise and thrust vectoring (US DoD). The limited number of missiles carried exacerbates the problems arising from the limited ability of even later variants of the AIM-120 to deal with high G manoeuvring targets, equipped with advanced DRFM jammers. The AIM-120 was conceived to defeat massed raids by Soviet era tactical strike aircraft, which had limited manoeuvre performance and poor defensive systems, and could thus be picked off easily. While the seeker and propulsion in the AIM-120 have evolved considerably since the AIM-120A, its basic aerodynamic design and flight profile are not adequate to kill a high G manoeuvring late model Flanker. Claims that the AIM-120 has killed manoeuvring targets in trials should be assessed carefully, since the US has no drone aircraft which can aerodynamically match the supercruising thrust vectoring and extremely agile late model Flanker. While seeker improvements, and derivative AIM-120 designs equipped with other seekers, such as derivatives of the AGM-88 and AIM-9X designs, would overcome the susceptibility of the active radar seeker to DRFM jammer technology, they cannot overcome the inherent aerodynamic limitations of the AIM-120 airframe design when confronting high G manoeuvring targets. Where a missile's ability to kill a target is uncertain, the basic strategy to overcome this limitation is to fire salvoes of two, three or four missiles against a single target. The Russians have adopted this model with the later Flanker variants, typically carrying up to twelve Beyond Visual Range missiles. This permits six two round salvoes, four three round salvoes or three four round salvoes for an especially difficult target. With two, maybe four missiles, the Joint Strike Fighter cannot play this game, and will never be able to do so. It is now abundantly clear that the Joint Strike Fighter is not going to be viable in Beyond Visual Range air combat, just as it was clear from the outset that it would never be a serious player in Within Visual Range air combat. Improvements in the capability and number of internally carried missiles will not turn this problem around, since the opposing sensor and weapons capabilities will continue to evolve over time. The remarkable claims about Joint Strike Fighter air combat performance made recently by the program executives and manufacturer's public relations staff can be explained only if the cited simulations were conducted against 1980s Russian Sukhoi variants, devoid of the tactics, sensors, weapons and supporting systems contemporary and future Flanker variants will employ. As such these claims clearly lack analytical rigour and cannot be taken seriously. |

|||

|

|

|||

| |

|||

Imagery

Sources: Author; www.jsf.mil, US DoD.

|

|||

|

Air Power Australia Analyses ISSN 1832-2433 |

|||

|

|||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

|||||||||||||

| Artwork, graphic design, layout and text © 2004 - 2014 Carlo Kopp; Text © 2004 - 2014 Peter Goon; All rights reserved. Recommended browsers. Contact webmaster. Site navigation hints. Current hot topics. | |||||||||||||

|

Site Update

Status:

$Revision: 1.753 $

Site History: Notices

and

Updates / NLA Pandora Archive

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Tweet | Follow @APA_Updates | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||