|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433] Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433]](APA/APA-Title-Analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433] Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433]](APA/APA-Title-Analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| National Military Strategy and the Defence 2008 White Paper |

|||

|

|||

The Russian designed Sukhoi Su-30MKI

Flanker H long range

fighter-bomber is characteristic of the deep transformation taking

place in Asian military capabilities. As Asia industrialises its

economies, increasing wealth is resulting in increasing technologically

sophisticated and potent military capabilities (US Air Force image).

|

|||

IntroductionAustralia is at an important strategic crossroad. If the right choices are made, Australia can enjoy a strong strategic position in the Asia-Pacific-Indian region, with all of the benefits that entails. If the wrong choices are made, Australia's strategic position in the region will continue to decline, with all of the risks and costs that entails. Inevitably, the question must arise as to what these right choices are, in terms of national military strategy and in terms of the ADF force structure and capabilities required to execute that strategy. Strategy is inherently a very long term game of positioning. Those involved develop capabilities which provide them with the ability to perform specific tasks, or deny opponents opportunities to perform specific tasks. Those specific tasks vary widely, as widely as the spectrum of military operations seen in conflicts between nation states, and more recently, conflicts with non-state entities. For Australia, the basic strategic calculus is simple: what strategy and force structure provides the most robust strategic position in our region, yet does not incur unreasonable material expenditures, is not too confronting to our neighbours, nor imposes unwanted constraints upon other military options on the global stage? Much of the public strategy debate in Australia since 9/11 has been dominated by the idea that the Global War On Terror is a genuine existential threat to Western civilisation and indeed to Australia, and that this conflict with its global deployment demands must take priority over other strategic needs. There is little doubt that the intent of the Islamofascist movements that are at the core of the GWOT is to be an existential threat to the West, and to be treated as such. This ambition is however not matched by capabilities. Since 9/11 the Islamofascist revolutionary warfare movements have taken significant losses, especially in leadership cadres, and in territory controlled or owned. Key strategic aims, such as the toppling of secular governments in the Islamic world, have not been achieved and are much further out of reach today than a decade ago. The only circumstance under which Islamofascism can be considered to be a genuine existential threat to Western civilisation is should these movements gain access to robust nuclear and biological weapons capabilities – and delivery systems. A dozen nuclear bombs is not enough to bring down Western civilisation, or any major nation state power bloc for that matter. Hundreds of nuclear weapons would be required for that purpose. The notion that Islamofascist terrorist movements will be able to acquire, maintain and deploy such numbers of nuclear weapons, even with the active support of like minded nation states such as Iran, is difficult to accept. What is abundantly clear is that Western civilisation will need to continue this conflict until Islamofascism burns itself out, just as 1930s fascism and Soviet communism did. For Australia this conflict cannot be the primary focus of national strategic policy and force structure planning. At best it is a secondary priority. Another theme which has occupied disproportionate attention in Australia's public debate on strategy is the “Arc of Instability” which spans developing nations from the Middle East through to the Pacific island nation states. Australia has had little choice other than to commit military and civilian personnel to a number of peace enforcement, peace keeping and stabilisation operations over the last decade. In grand strategic terms, the “Arc of Instability” and the GWOT share one common set of features. They are products of the post Cold War world in which the competitive purchasing of allegiances by the West and the Soviet Bloc through economic and military aid, a practice which pervaded the four and a half decades of the Cold War, has vanished to the detriment of the economies of nations which were recipients of such material support. This has been exacerbated by the effects of globalisation, where increasingly, wealth has concentrated in nations with developed economies and institutions. Developing nations which were able to sustain themselves during the Cold War era are more than often unable to maintain themselves, creating power vacuums which have been filled by a range of political, religious, ethnic/tribal movements or groupings. Internal conflicts and institutional collapses across the “Arc of Instability” are not an existential threat to Australia, although they may produce strategic opportunities for other nation states to improve their strategic position within Australia's area of geographical interest. As is the case with the GWOT, Australia will need to continue its involvement in operations intended to stabilise nations or localised regions which are suffering internal problems across the “Arc of Instability”, and maintain required capabilities. Similarly, such conflicts cannot be the primary focus in Australia's national strategic policy and force structure planning. At best such operations are another secondary priority. The biggest strategic issue Australia must grapple with is the industrialisation of Asia and the resulting military growth, especially in long range weapon systems capable of reaching Australian territory or its geographical areas of interest. At the end of the Cold War in 1991, there were four major centres of gravity in the global economic machinery. These were the United States, the European Union, Japan and the rapidly disintegrating Soviet Comecon Bloc. Most of the world's economic activity and wealth were being generated and concentrated in these four nodes. The world is very different now. The United States and the European Union remain as major centres of gravity in the global picture, the Soviet Bloc has effectively dissolved, but North East Asia has replaced it as a significant centre of gravity. The industrialisation of Japan has peaked, South Korea is approaching its peak, while China and other Far Eastern nations have yet to peak. India is following much the same pattern as nations in North East Asia. In the most basic sense, what we are observing now is an ‘Arc of Industrialisation’ stretching from South Asia to Japan, in much the same pattern observed in North America and Europe a century ago: industrialisation produces national wealth, which is invested into national economies, infrastructure, institutions, military forces and national education. The “end state” of this industrialisation process is a “modern” nation state with well developed infrastructure, economy, institutions, military forces and a well educated population. There is little doubt that much of what is fuelling this growth in Asia are individual and national ambitions of becoming “like the West” - or in simpler terms, becoming wealthy, comfortable, secure and globally respected. The path to this end state was not an easy one for the West, involving two World Wars, a four and a half decade long Cold War, and the moral abominations of Fascism and Communism along this path. The notion that Asia can arrive at the same end state as the West, but without the kind of turmoil seen during the twentieth century is optimistic, but it is also a goal which should be actively sought by Asian nations and the West alike. The scale and patterns of military spending across Asia since the end of the Cold War are much more indicative of the type of unfettered nationalism-driven competitive arms race which helped produce the two World Wars in Europe. The pivotal strategic consequence of this, for Australia, is that nations in Asia are acquiring and deploying capabilities which, for the first time since the 1940s, will provide the ability to strike at Australian territory and within Australia's regional area of interest. The most important strategic imperative for Australia in coming decades will be to acquire and maintain military capabilities which make the prospect of military conflict with Australia unattractive to any nation in Asia. |

|||

Asia's "Arc of

Industrialisation" presents

a

parallel trend to the "Arc of Instability", a term coined by Prof Paul

Dibb some years ago. What we are observing in Asia is analogous in one

sense to what we observe in North America and Europe - wealthy

industrialised nations neighboured by poor agrarian and pre-industial

nations, the latter more than often with weak institutions and domestic

movements

or groups contesting the power of the nation state.

Military Capability Growth in AsiaMuch has been written and said about military capability growth in Asia over recent years. More than often it is described as “modernisation” and uncritically accepted as no more than the natural evolutionary process of replacing obsolete equipment with new equipment. This view of what has happened in many parts of Asia has proven very popular but it is at the most fundamental level, deeply misleading. This is because obsolete equipment is mostly being replaced with new equipment of more than often fundamentally different capability. Frequently we observe equipment designed for local area defensive operations being replaced with equipment built to project power and the associated destructive effect over a much greater range. This has been observed both in naval fleets and air forces across Asia. When the Soviet Union collapsed, only two nations with a military presence in Asia had the capability to deliver nuclear or conventional attacks of substance over distances of well over a thousand nautical miles. These nations were the United States and the Soviet Union. Less than two decades later, several nations in Asia have the ability to deliver strikes, using ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, or air delivered guided bombs, over distances of well over a thousand nautical miles. This is a fundamental and profound change in where the region sits in the global constellation of military power. Several capabilities are becoming prominent as a result: Air Launched Cruise Missiles: China, Pakistan and India have programs based on indigenous and/or Russian missile technology. China has several designs and is developing the indigenous H-6K Badger bomber to carry such missiles to targets at ranges well beyond 2,500 nautical miles. Sub/Ship Launched Cruise Missiles: China and India have programs based on indigenous and/or Russian missile technology. The Russian Club / SS-N-27 Sizzler has been supplied to both nations, and will likely be supplied to most nations procuring Russian submarines. Ballistic Missiles: China, North Korea, India and Pakistan have a range of ballistic missile programs, spanning tactical, intermediate/theatre and in some instances, strategic range categories. China is expanding its fleet of ballistic missile armed submarines, equipped with the JL-2 SLBM. Long Range Strike Aircraft: Russian designed Sukhoi Su-27/30 Flanker family fighter aircraft are becoming the most numerous type in the region, and with aerial refuelling support these aircraft can easily strike targets at ranges beyond 1,000 nautical miles. China and India have negotiated with the Russians for surplus long range Tupolev Bear and Backfire aircraft, although none has been exported to date. China is developing its indigenous H-6K Badger bomber. Aerial Refuelling Tanker Aircraft: China, India, Japan and Singapore have procured a range of different aerial refuelling aircraft. These can extend the reach of fighters and bombers well beyond 1,000 nautical miles. Fixed Wing Aircraft Carriers: India is currently recapitalising its aircraft carrier fleet and embarked air wings, the latter with the MiG-29K Fulcrum. China is refurbishing the former Soviet Varyag and procuring a wing of Su-33 Flanker D strike fighters. There can be no doubt that these nations are emulating the United States' and former Soviet models for the long range projection of coercive striking power. The success of the United States in air wars since 1991 has presented a clear template for nations in Asia to follow. While China and India are clearly the most prominent in the quantities and the sophistication of long range weapons procured, planned or deployed, they are also seen as “trend setters” in Asia, and their acquisitions have been and will be emulated, relative to budgetary capacities, by smaller nations in the region. The history of Flanker fighter sales across Asia is an excellent example. The Kilo class SSK is another. The trend to acquire weapons systems built to strike hard at increasingly greater ranges is paralleled by increasing technological sophistication in the types of weapons being acquired across Asia. Russia's extensive and capable defence industry has played a major role in this, both as an exporter of equipment, services and munitions, and as provider of basic technology for collaborative and/or licenced manufacturing programs. Of particular concern is that many of these Russian weapons outperform their US and EU equivalents. Many have no equivalents, a good example being Russian supersonic cruise missiles. Driven by market demand, Russian industry has aimed to develop and refine a wide range of capabilities, many of which are specifically designed to symmetrically or asymmetrically frustrate or defeat key US and other Western capabilities. US stealth capabilities are now being challenged by Russian two metre band VHF digital radar equipment, and networking of passive sensors and radar equipment. US precision guided bomb and cruise missile capabilities are now being countered by a wide range of guided missiles, and the development of directed energy weapons technology. In addition China has a well established program to develop and deploy high power laser directed energy weapons for this exact purpose. US Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities are being countered by a range of weapons, especially very long range air-to-air missiles and surface to air missiles. In addition, China has developed and tested an anti-satellite weapon based on the DF-21/JL-2 ballistic missile airframe, and has experimented with high power laser directed energy weapons for this purpose. While the compilation of detailed and exact statistics is, at times, tedious, there is more than ample evidence to show that both the numbers and sophistication of modern weapon systems deployed across Asia, or being procured, challenges and in many categories exceeds the capabilities deployed by the Soviets and Warsaw Pact nations in Europe at the end of the Cold War. This is especially true of top tier fighter aircraft like the Flanker, cruise missiles, and smart munitions. As many of these programs have yet to fully mature and complete deployment, the final tally will comfortably exceed the Cold War end state capability. What is clear beyond any doubt or dispute is that the period of 2015 and later will be characterised in this region by the widespread use of long range weapons, such as cruise missile armed aircraft and submarines, air delivered smart munitions, and supporting air capabilities such as tanker aircraft and Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C) Aircraft. A critical strategic imperative for Australia will be to have and present the ability to decisively and rapidly defeat any opponent armed with modern high technology weapons, especially long range high performance fighter aircraft, cruise missiles and smart munitions. |

|||

With India recapitalising its aircraft

carrier fleet, and China developing a fleet, regional nations are

gaining genuine power projection capabilities across the region.

Depicted Russian Sukhoi

Su-33 Flanker D fighters on a carrier flight deck (KnAAPO).

Regional Strategic RisksIt is fashionable in some analytical communities to treat strategic risks in Asia in a piecemeal fashion, by looking at specific historical disputes, current or ongoing disputes, and potential disputes between specific nations. While there is some merit in exploring such specific cases, this approach can rapidly lose sight of the larger picture in such a geographically extensive, culturally diverse, complex and rapidly evolving region.Asia parallels Europe in the reality that almost every nation has, over time, been embroiled in various disputes or even armed conflict, over territorial boundaries, with its neighbours. The neo-Clausewitzian perspective is that this behaviour is characteristic of nation states and is thus an unavoidable but ugly reality. Industrialised nations survive on resources and energy to feed their industries, and on markets for their products. Many, and arguably most of the wars observed between Western nations during recent centuries have directly or indirectly revolved around competition for access to resources and/or markets. While some conflicts have presented as disputes over ideology, the Cold War being the prime example, the ideology itself was more than often little more than a facade to conceal greed for material resources and population access i.e. markets. With the depletion of easily accessible fossil fuels due to sharply rising global demand, security of energy resources will become an increasingly important consideration for Asia's strategic planners. Whether we are dealing with crude oil, natural gas, or coal derived products, industrialised nations have a long history of conflict over security of energy supplies. Security of supply of raw materials for manufacturing economies has followed a similar pattern to disputes over energy resources, and Europe's abundance of coal to fuel its manufacturing economy over much of the last two centuries has tended to skew the relative importance of raw materials versus energy supply. Competition over access to markets has also been a factor in a range of disputes over recent centuries. The notion that an industrialised Asia, with its fundamental dependency on imported energy, raw materials and its need for markets, will be immune to the pressures which led to so many conflicts in the Western world, can only be said to be optimistic. A good case study is presented by China and India, both of which have been negotiating access to supplies of natural gas from Iran. Iran, with its abominable human rights record, long running history of sponsoring terrorism, and a defacto pariah state due to its nuclear ambitions, could hardly be said to be a politically attractive trading partner for India, a robust democracy, and to China, preoccupied as it is with cultivating its public image on the global stage. Yet both of these nations have been seeking access to Iran's gas, in the full knowledge that revenue going to Iran will be used to further Iran's ambitions for regional power. China's ongoing disagreements with Japan are often presented in the light of Japan's lack of repentance for World War II activities in China, yet the most prominent aspect of this dispute is competition over seabed energy resources located along economic zone boundaries. The long running multi-partite argument over the Spratley Islands fits a similar pattern. The strong investment being made by both China and India in naval capabilities, and long range air power, is characteristic of perceived and/or actual strategic pressures to protect vulnerable lines of supply for energy resources. While there is considerable potential for conflicts in Asia to arise over ideological, religious and ethnic disputes, such as the long running disputes between India and Pakistan, or North and South Korea, or North Korea and Japan, or China and Taiwan, the greatest risk of escalated conflict will arise where access to energy, raw materials and markets will be at stake, as these are fundamental to the economic wellbeing and, ultimately, the survival of industrialised nation states in a highly competitive globalised economy. This analysis looks at this problem from the perspective of “strategic risk”, rather than the more traditional model of “threat”. The threat based view of strategic problems is predicated upon the equation of “threat = capability + intent”. This approach to looking at strategic problems was well suited to situations like the Cold War, where the Soviet Bloc had both capabilities and a declared intent which was essentially hostile to Western civilisation, and neither of these circumstances changed fundamentally between 1945 and 1991. Asia presents a far more dynamic reality for coming decades. Economies will grow, military capabilities will grow commensurately, strategic agendas and interests will change, as will alignments and alliances. Intent will therefore change continuously, and cannot be reliably predicted even in the shorter term. It is unlikely that we will ever see a simple strategic picture as during the Cold War, of two monolithic and mutually opposed blocs, with overtly stated intent, and diametrically opposed ideological and philosophical views of the world. The important strategic consideration for Australia is that as the military reach of nations in Asia expands, and their militaries become more capable, and better educated and trained, Australia will need to adopt a far more dynamic model for developing and maintaining military capabilities compared to past decades. Australia will also need to systematically benchmark its own capabilities, and planned capabilities, against a range of regional capabilities, to minimise risks to Australia and its interests. In pragmatic terms, Australia needs to adopt much the same model of strategic planning and capability development practiced by the United States during the Cold War, where capabilities which altered the strategic balance were systematically and rapidly countered to minimise strategic risks. |

|||

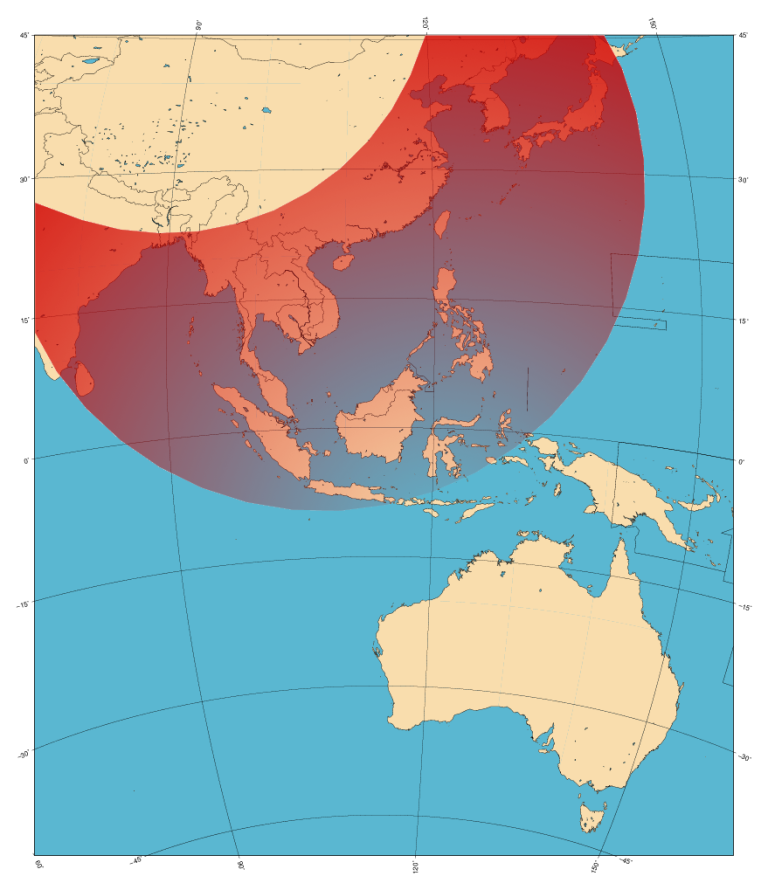

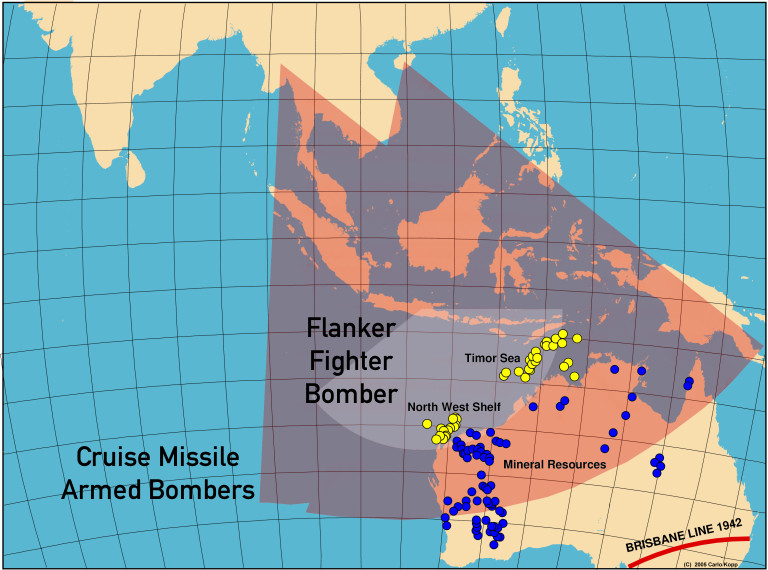

One of the critical byproducts of the

transformation of military capabilities across Asia is that older short

range weapon systems are being replaced by systems with significantly

greater reach, which for the first time since the 1940s places

significant portions of Australian territory and its area of interest

under the footprint of foreign military air forces. The depicted

footprint labelled "Cruise Missile Armed Bombers" is representative of

types such as the Xian H-6K turbofan Badger and Tupolev Tu-22M3

Backfire. The coverage depicted for the Flanker excludes aerial

refuelling support. Greater reach has coincided with a greater economic

dependency in Australia upon energy and mining resources across the

north and north-west of the continent (C. Kopp).

|

|||

China's Military GrowthWhile

most of the trends in economic and military growth observed across

Asia are generally true for all nations actively pursuing

industrialisation of their economies, China deserves additional

discussion for a number of important reasons.

The first is that China has made the greatest investment in force structure of any nation in Asia, and has embarked on constructing a military machine which is clearly intended to rival that of the United States in Asia. The second is that China has a well developed national military strategy and associated force structure plan, which has been well articulated and is being followed meticulously. The third is that China presents a major strategic risk of future conflict in the region. This is due to China’s stated intent to use force to seize Taiwan, backed by the size of its military with its increasing technological capabilities, which could result in a major conflagration should hostilities arise. Much has been said about the “rise of China” and its transformation from an agrarian economy to a major industrial powerhouse and military power on the global and regional stages. Predictions of China's future economic and military growth vary widely. Factors which favour ongoing long term growth include an increasingly well educated population, which is highly industrious and mostly cohesive and nationalistic, as well as a shared national ambition to become a major economic and military power on the regional, if not global stage. Factors which will impede long term growth include high levels of dependency on foreign markets, these including investment funding, a communist era legal code with underdeveloped property law and poor provisions for managing debts and civil disputes, and a communist era public service bureaucracy which will increasingly have to confront the complexities of managing a modern economy and nation state. In a sense China's rise parallels that of Germany during the 1930s, as it has been fuelled by foreign investment borrowings and massive industrial growth, resulting in unprecedented levels of urbanisation and demonstrably, social dislocation. China confronts a range of internal risks, associated with its economy, infrastructure, internal institutions, disaffected minority ethnic and religious groups, and deep and pervasive mismatches between its communist era machinery of state, and its increasingly modern capitalist economic system. The Communist Party leadership's obsessive preoccupation with Taiwan represents an unnecessary distraction from solving far more important problems centred in China's development of modern governance systems and a more representative system of government. Many scenarios can be developed for how China could become embroiled in conflicts with its neighbours and/or the United States. The common thread which runs through all of these scenarios is that as China's military power increases relative to the US and other regional nations, there is an increasing risk that a future Chinese leadership group may perceive the use of force as a viable choice in foreign policy. A detailed discussion of China's military growth and strategic thinking exceeds the scope of this paper. Several fundamental factors are, however, of importance. The first is that China has defined a strategy for developing and deploying its military capabilities within the region. This is the “Second Island Chain” strategy which aims to deny the use of, or access to, basing which could be used to attack, bombard or blockade China during time of conflict. The “Second Island Chain” runs through Japan, the Marianas, Papua New Guineau, Northern Australia, Indonesia and the Andaman Islands. Targets along the “Second Island Chain” sit at radii between 1,500 and 2,500 nautical miles from basing in mainland China. China has been developing a range of capabilities intended to support the “Second Island Chain” strategy.

The

“Second Island Chain” strategy is supported by a further

strategy, often labelled the “String of Pearls” strategy,

whereby China via military and economic aid cultivates regional

nations along the “Second Island Chain” to deny basing to

other nations, or to gain basing for PLA assets. The extensive

military infrastructure constructed in Myanmar (Burma) is consistent

with this model. The cultivation of East Timor, and some Pacific

Island nations, via economic aid, is also consistent with this model.

There is little doubt that China sees its principal strategic competitor in Asia to be the United States. The preoccupation with defeating specific US capabilities, and the “Second Island Chain” and “String of Pearls” strategies are both centred on denying the US basing which could be used in a conflict against China, and defeating those key US capabilities which have been central to US victories in recent conflicts. In addition, these capabilities provide significant coercive and deterrent capability against India and Japan, both of whom China has at various times considered regional competitors. China's military growth is of pivotal strategic importance to Australia for a variety of reasons. One is that China may opt at some stage to challenge the US presence in Asia, so as to surround itself with compliant smaller nations as a strategic buffer. Arguably this is an established aim of current strategy. Another is that China's unrelenting military growth will continue to stimulate military growth across Asia, resulting in ever increasing capabilities across Asia as smaller nations seek to counter perceived or real coercive capabilities deployed by China's PLA. Perhaps the most important is that full implementation of the “Second Island Chain” and “String of Pearls” strategies and associated force structure elements will provide China with significant coercive striking capability against Australia, as well as the capability to project power into Australia's sea-air gap. In pragmatic terms, China's strategic agendas will clash with Australia's long established strategic agenda of maintaining control of the air and sea over the north of the continent, and the sea-air gap. Australia must face this matter as a priority in its national military strategy and its force structure, as diplomatic posturing will become totally irrelevant if a future Chinese leadership chooses to exercise its military options against Australia.  Hainan Island is a critical element in the

'Second Island Chain'

strategy, as it would provide basing for combat aircraft and submarines

operating into

the Indonesian Archipelago, the Australian 'Sea Air Gap', and the

approaches to Guam. Hainan Island has six airfields, three are

semihardened / hardened fighter bases, and three are dual use civil

airports, two of which have 11,000 ft runways capable of accommodating

long range aircraft. Burma with four runways which exceed 11,000 ft

length supplements Hainan Island, covering the Western arc out of South

East Asia through the Andaman Islands. A major underground submarine

base is now under construction at

the southern tip of Hainan Island (Map - C. Kopp).

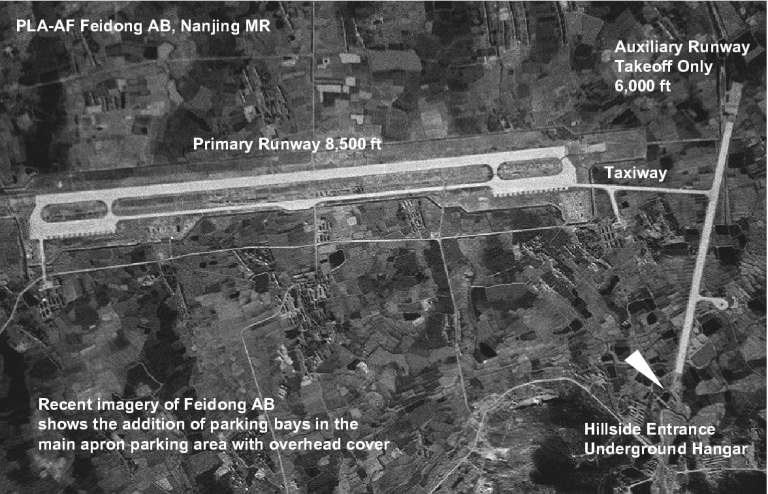

The PLA-AF fighter base at

Feidong in the Nanjing MR [Click for more ...] is a good example of the design of a

'superhardened' fighter base. The primary runway , available for

takeoffs and landings, has a wide full length parallel taxiway to

enable

recoveries in the event of damage. An auxiliary take-off only alert

runway is directly connected to the underground hangar entrance,

allowing the fighter to roll out of the tunnel, line up, open the

throttles and take off quickly. The PLA invested considerable thought

into planning its network of 'superhardened' fighter bases, usually

placing the runways behind a hill or mountain, relative to the threat

axis. Another good example of such a base is at Yinchuan [Click for more ...] in the Beijing MR. While modern

smart

weapons have diminished the effectiveness of such base designs, they

still present genuine challenges in targeting and achieving robust

weapons effects (US DoD).

|

|||

Andersen

AFB, at the northern tip of Guam in the Marianas island chain, is a

strategically critical basing site for the US Air Force in the West

Pacific (WESTPAC) region. With the large scale proliferation of a

precision guided munitions in the region, including cruise missiles and

terminally guided ballistic missiles, the absence of modern hardening

measures, a weakness shared by other US basing in the region and

RAAF basing in the north of Australia, presents a major

survivability issue for this base in any escalated regional contingency

(US Air

Force image).

The United States Presence in AsiaThe

United States has been the dominant power in Asia since the defeat of

Japan in 1945. During that period the US had a large network of naval

and air bases across the Pacific, constructed to support the aerial

bombardment, naval blockade and eventually, the planned but never

executed invasion of the Japanese home islands.

Much

of this basing infrastructure remained in use through the Cold War,

and was employed extensively during the Korean War and Vietnam

conflict. Since the end of the Cold War, and the subsequent Base

Realignment And Closure (BRAC) program, the US basing infrastructure

in the Far East has been reduced. The single largest loss in

capability resulted from the US withdrawal from the Philippines,

which saw the loss of both Clark AFB and the Subic Bay naval base, as

well as a wide range of other supporting facilities.

Andersen

AFB, Guam, and Naval Base, Guam, in the Marianas. These are the

remaining elements in the large cluster of airfields and supporting

infrastructure in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

(CNMI), including the basing on Tinian and Saipan islands. Training

facilities at Saipan, Rota, Tinian and Saipan Harbour are available

for US military usage.

Osan

Air Base, Pusan Anchorage and 2nd Infantry Div basing in

South Korea. These are the remainder of more extensive basing

developed during the Korean War and sustained through the Cold War.

Okinawa,

in the Ryukyu Islands, Japan. Okinawa hosts Kadena AFB, and a

range of US Marine Corps basing and training areas.

Misawa

and Yokota AFBs, Atsugi, Yokosuka and Sasebo Naval Facilities, Japan. This

basing is primary to provide logistical support for

US forces in

Asia, although the Yokosuka is used to home port US aircraft

carriers.

Hickam

AFB and Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Hickam provides permanent basing

for fighter and transport aircraft, and the Kenney Warfighting

Headquarters facility. Pearl provides basing and a shipyard.

Until

recently, the US Navy's carrier battle groups provided a critical

component of US deterrent capabilities in the Asia-Pacific region.

Increasingly, these are becoming irrelevant in the face of developing

capabilities in Asia, especially capabilities being developed by

China.

Aircraft

carrier battle groups defended by F/A-18 Hornets and Super Hornets,

and guided missile cruisers and destroyers, will not have a credible

capability to defend themselves against saturation attacks by more

capable land based Flanker fighters, or cruise missile armed bombers

and submarines. The capabilities being developed and deployed across

Asia, especially those being developed and deployed by China, rival

or exceed the capabilities of the former Soviet

naval strike forces.

With the loss of the F-14 Tomcat fighter, the US Navy no longer has

the “outer air battle” capabilities

created during the

Cold War to defeat such threats.

While

the US Air Force has the highly capable B-2A Spirit bomber and the F-22A Raptor multirole fighter, and

will have the planned “New

Generation Bomber” post 2020, it faces several key problems in

maintaining its position in Asia.

The

first is that the United States does not have enough runways and

basing infrastructure across Asia to deploy credible strength in the

numbers needed to deal with anything beyond medium level

contingencies. A second associated problem is that what basing exists

is “soft” and highly vulnerable to attack

using smart

bombs, cruise missiles or terminally guided ballistic missiles. A

third associated consideration is that most basing within close range

of potential flashpoints, such as Taiwan, is within the footprint of

a wide range of weapons types.

A

factor underpinning problems with basing is that current US planning

is not providing for sufficient numbers

of F-22A Raptors to prevail

in any major conflict in Asia. This is exacerbated by block

obsolescence problems across much of the current US fighter, aerial

refuelling tanker and heavy bomber fleets. A further problem is that

the Joint Strike Fighter, of which

around 800 are planned for the US

Air Force, is completely unsuited

to the type of conflicts likely to

be seen in Asia. US efforts to recapitalise its Air Force fleets have

been frustrated repeatedly by strategic

overstretch, associated

budgetary problems arising from the Global War On Terror, and more

than often by political meddling by industry seeking to promote their

strategically irrelevant and less than capable equipment programs.

To claim that the United States

is a

“spent power” and “has lost its strategic

pre-eminence in Asia” is premature,

however this is a real and, therefore, significant risk. The

US has many options still available

to reclaim its strategic

advantage in Asia. However, these will need robust and rapid

investment, a major political challenge given the US budgetary

situation and continuing demands of the Global War on Terror.

Australian

Governments have long given lip service to the need for Australia to

develop a sound measure of self-reliance in combat and support

capabilities. This is to demonstrate Australia's willingness to pull

its weight in concert with its allies and to demonstrate a real

capability to conduct military operations in Australia's area of

interest should Australia's allies, especially the US, not be able to

provide support to Australia when needed. The developments that we

are seeing throughout our region make the need for genuine Australian

self-reliance much more urgent.

The

key strategic consideration for Australia is that there is no

guarantee at present that the US will make the necessary investments

in force structure to retain its long term strategic position in the

Western Pacific region. As a result, the deterrent capabilities the

US could apply in the past may no longer be effective, leaving US

allies like Japan and Australia largely exposed and having to rely on

their own capabilities in any future regional conflict of any

substance.

|

|||

|

A major strategic problem the US faces is block obsolescence across its fleet of Cold War era combat aircraft and aerial refuelling tankers. The fiscal pressures of the protracted Global War On Terror have severely impacted the recapitalisation of the US Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps aircraft fleets. Current planning for the US Air Force fighter fleet restricts the number of F-22A Raptor fighter-bombers to around 180 aircraft, as a result of which it is unclear that the US could retain air superiority in any escalated contingency in Asia. The video shows F-22As on a bombing exercise flying from Guam, the weapons deployed are GBU-32 JDAMs (US Air Force). |

|||

Defining a National Military StrategyRecent Defence White Papers have centred Australia's national military strategy in the denial model, which essentially amounts to denying any regional opponent control of the sea-air gap to the north of Australia, control of airspace over the Deep North, and where applicable, denying the use of air and naval basing in the archipelago to the North.This is a sound model, born from the experience of World War II, when the Japanese used the Indonesian archipelago to base bomber and fighter aircraft used in attacks against Australian cities, ports, basing and shipping in the North and the sea-air gap. This model is centred in the realities of Australia's geography, and historically constrained by the capabilities of power projection weapons such as bomber aircraft which were limited mostly to ranges of the order of 1,000 to 1,500 nautical miles. Much has changed since the 1940s, and all of these changes have increased the importance of focussing Australia's national military strategy on the defence of the North and the sea-air gap. The first change of pivotal importance has been the economic development of the north and the continental shelf. Australia's resource industry now accounts for a very much larger fraction of national export earnings than it did six decades ago, and much of that industry is located in the North-West, the Northern Territory, and Queensland. A regional opponent opting to shut down this industry could inflict significant economic damage very quickly, and possibly with long term impact if key infrastructure is heavily damaged. Parallel to the development of the mining industry, the oil and gas industries have flourished across northern Australia. With major facilities at the Burrup Peninsula and Barrow Island, exploiting North-West Shelf oil and gas, and the development of the Timor Sea reserves via facilities in the Northern Territory, Australia now has a major export revenue source, and domestic energy supply source, centred in the north. As with other components of the resources industry, closure of the energy industry as a result of hostile military operations could inflict significant loss of national revenue. A no less important consideration is the increasing dependency of other industries on gas supplied from the north. Western Australia has suffered repeated economic losses across a range of industries as a result of accidents impairing the flow of North West Shelf gas to consumers across the state. Tourism, across the north of Australia and Queensland, has become another important source of national revenue, and it is another industry which would suffer heavily in any circumstance where sea and air lanes in the North, as well as population centres, could be threatened by military action. Importantly, many of these industries would have to shut down, or severely curtail operations, were they to be subjected to the threat of air or cruise missile attack, even if these were relatively small “harassment raids”. The gas and oil industry is especially vulnerable to attack by guided munitions and cruise missiles [1]. The confluence of Australia's economic growth across the north, and military growth across Asia, results in Australia becoming increasingly exposed to the potential for coercive military operations aimed at inflicting economic damage. Unlike the World War II and Cold War era, where a regional opponent would have to base assets in the Indonesian archipelago to reach northern Australia, many of the capabilities now deploying in Asia and/or planned for deployment can bypass this geographical constraint completely. Operating directly from bases on the Asian mainland, long range bombers armed with cruise missiles and submarines armed with cruise missiles or ballistic missiles will have the capability to hold at risk most potential targets of interest in Northern Australia. Many such systems will be capable of also threatening Australian population centres along the southern and south-eastern coastlines. This is the most profound change in Australia's strategic circumstances since the 1940s, and a change which must be reflected in national military strategy and force structure planning, if the Australian Defence Force is to have any future relevance to the national defence. A question often asked is whether any capabilities the Australian Defence Force could deploy and operate could actually make a real difference, were Australia confronted by the upper tier of regional capabilities in a conflict. |

|||

Australian exports by industry. The mining

and energy sectors represent an important source of export revenue for

the Australian economy, a trend which is likely to increase over time

especially as global demand for energy soars, and further energy

resources are developed (Chart by Australian Bureau of Statistics).

Western Australia and Queensland generate

most of the nation's export revenue through mining, including ores,

minerals, coal, oil and gas. The growth in this industry sector across

the north of the continent has resulted in a major economic

vulnerability to disruption (Chart by Australian Bureau of Statistics).

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (above) and

F/A-18F Super Hornet (below) are both completely unsuited to the

strategic realities Australia must now confront. Neither aircraft has

the performance or survivability to confront the advanced Russian

designed fighter and missile systems now extant and also planned across

Asia. In practical terms these aircraft will only be viable for

training, close air support and counter-insurgency operations (US DoD

images).

|

|||

This

is dependent upon two factors. The first is whether Australia invests

in the right type of capabilities to deal with such threats. The

second is that no regional nation can afford to bear significant

combat attrition in capabilities such as long range combat aircraft

or submarines, without losing much of its strategic potential. If

Australia invests robustly in capabilities which can inflict

significant combat attrition against hostile combat aircraft and

submarines, the cost of exercising coercive power against Australia

will be driven up significantly. If Australia's capabilities are seen

to be capable of inflicting serious attrition on such forces, a

deterrent effect will result.

In strategic terms this means that Australia should centre its future military strategy on “regional denial” with the aim of denying operations in the sea-air gap, above and around the Australian continent, and also denying the basing of combat forces and facilities in the northern archipelago. To implement such a strategy, Australia will need to fundamentally rethink its approach to air power, naval power and land force capabilities. Current and future capabilities for the RAAF will need to be focussed in two key areas. One is persistent air dominance and the related capability to kill cruise missiles and their launch platforms. The second is in providing long range strike capabilities with sufficient weight of fire to render regional basing unusable in combat. Maritime patrol and Anti-Submarine Warfare capabilities need a complementary focus and will also require growth. Current and future capabilities for the RAN will also need to be focussed in two key areas. The first is in Anti-Submarine Warfare, requiring surface combatants and submarines which are suitable for this task and sufficiently numerous. The second capability is in providing organic cruise missile defences for surface warships and escorted shipping. Current and future capabilities for the Army will need to include Surface to Air Missile, and in the future Directed Energy Weapon, defences against cruise missiles, ballistic missiles and other guided weapons, to protect critical military and industrial infrastructure, and population centres. The Army will also need to assume responsibility for protecting such targets against Special Forces attack. Another important future role for the Army is providing covert insertion and extraction means for Infantry and Special Forces operating across the region. Sufficient capabilities should be available to deploy, sustain and extract useful numbers of Infantry and Special Forces troops. These are deep and fundamental changes against the hitherto planned capabilities for the RAAF, the RAN, and the Army. The RAAF's currently planned F-35 Joint Strike Fighter and F/A-18E/F Super Hornet aircraft are essentially battlefield interdictors and close air support fighters, and thus wholly unsuitable for the air dominance and deep penetration strike roles. The number and size of aerial refuelling tankers planned for the RAAF is completely inadequate to credibly support persistent air dominance, cruise missile defence and long range strike operations. The RAN's currently planned Air Warfare Destroyers are, by design, focussed on long range air defence of Surface Action Groups, rather than Anti-Submarine Warfare and cruise missile defence, and are too few in number. More numerous and smaller surface combatants, designed for Anti-Submarine Warfare and cruise missile defence, will be required. A larger number of replacement submarines for the Collins class will also be required, and given the range and persistence requirements of the role, options such as nuclear propulsion should be considered very carefully. The problem of Special Forces insertion, sustainment and extraction will require a more appropriate and complete solution, spanning fixed wing RAAF, RAN submarine, and Army rotary wing capabilities, or other technological alternatives. Similarly, the need to deploy and sustain army forces to defend infrastructure against precision guided munitions attack and special forces will require specialised new weapons, supporting equipment and personnel. The Army Reserve, which has access to good technological skills across the wider community, is a natural candidate for operating and maintaining Surface to Air Missile capabilities. Other, joint, capabilities will be required to support all three services in performing these roles. Robust strategic, operational and tactical Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities will be required. Strategic ISR will require a survivable airborne component, as well as persistent airborne components such as Uninhabited Aerial Vehicles (UAV). High capacity networking and digital communications capabilities will also be needed which exceed the simple expedient of additional satellite capacity. Electromagnetic hardening against nuclear EMP and microwave attack will also be necessary for critical Commonwealth computer and communications facilities. A technical intelligence collection and analysis capability of substance will be necessary. Specific capabilities for the rapid recovery from attacks against the infrastructure will also be necessary. The basing infrastructure of all three services, but especially that of the RAAF, will need to be hardened to withstand attack by precision guided munitions. This is most important for infrastructure in the north of Australia, and must encompass aircraft shelters, fuel storage and replenishment, munitions storage and command, control and communications facilities. Other facilities, such as materiel warehousing, need to be physically dispersed rather than physically concentrated. The drive for cost efficiency in material handling and storage is at odds with the military imperative of survivability, be it against attack by guided weapons, special forces, or saboteurs. A major consideration, now of strategic importance, is the cumulative impact of sustained long term deskilling, loss of talent, and erosion of professional mastery in the Australian Defence Organisation. No matter how good a fundamental national military strategy and resulting force structure might be, it will be ineffective if the personnel base lacks the skills sets to execute it effectively and sustain the required military capabilities. The strategic realities Australia will need to face over coming decades cannot be solved by incremental changes to the force structure model which has evolved since the Defence 2000 White Paper. Much of that model has been constructed on an ad hoc basis, or to reactively address short term needs identified by the Global War On Terror. Produced with no regard for the strategic direction in the Defence 2000 White Paper, the current force structure plan is a basic impediment to Australia developing the force structure and capabilities required to maintain its relative strategic position in a much more challenging, complex and dynamic region. |

|||

Imagery

Sources: Author; Rosoboronexport; Russkaya Sila; Ugolok

Neba; MilitaryPhotos.net; US DoD, Xinhua.

Copyright and Terms of

Use:

© 1998 - 2008 Carlo Kopp, Peter A Goon. These works have been developed for use by the Commonwealth of Australia in the Defence 2008 White Paper process and are proprietary to the founders of Air Power Australia. Permission is granted for use of this material, part or in full, including copying and reproduction, provided the requisite full rights of authorship and copyright are attributed to the founders of Air Power Australia. These works draw on proprietary material which dates back to 1998 for which, in the context of these works, the same permission is granted where applicable. Endnotes: [1] An analogous argument can be made for closure of sea and air lanes carrying other exports, and imports. Australia is more dependent now on technological imports, and sustaining the domestic economy would be difficult were these restricted or otherwise impaired. References and Bibliography:

|

|||

|

Air Power Australia Analyses ISSN 1832-2433  |

|||

|

|||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

|||||||||||||

| Artwork, graphic design, layout and text © 2004 - 2014 Carlo Kopp; Text © 2004 - 2014 Peter Goon; All rights reserved. Recommended browsers. Contact webmaster. Site navigation hints. Current hot topics. | |||||||||||||

|

Site Update

Status:

$Revision: 1.753 $

Site History: Notices

and

Updates / NLA Pandora Archive

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Tweet | Follow @APA_Updates | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||